Dark Universe: The Franchise That Tripped Over Its Own Cape

- Jan 31

- 21 min read

Universal tried to build an MCU with Dracula and forgot to make a good movie first

Once upon a time, Universal Pictures looked at the box office, looked at Marvel, looked at its dusty vault of iconic monsters—and said:

“What if we did that… but faster?”

Thus was born the Dark Universe, a cinematic experiment that answered the age-old question: What if you announced a franchise before anyone actually wanted one?

This is the story of how Universal’s bold monster megaverse collapsed under the weight of its own branding, PowerPoint energy, and deeply misplaced confidence. Grab your torch and pitchfork—we’re going in.

Prologue: When Movies Learned How to Be Afraid

Before superheroes could fly, before franchises had phases, and long before anyone argued about “cinematic universes” on the internet, movies discovered something far more powerful:

Fear.

In the early decades of Hollywood—when sound was still a novelty and movie monsters had to earn their screams without CGI—Universal Pictures quietly built the foundation of modern pop mythology. Not with capes or quips, but with shadows, lightning, and the slow realization that cinema could make audiences confront the things they were already afraid of.

These weren’t just scary movies.They were the first shared language of horror.

Hollywood’s First Monsters Were Born Out of Anxiety, Not Spectacle

The Universal Monsters emerged in the early 1930s, right as the world was unraveling.

The Great Depression had shattered economic certainty. World War I still haunted the global psyche. Science was advancing faster than morality could keep up. And suddenly, movies had sound—voices that could whisper, scream, and seduce.

Universal leaned into the moment.

With Dracula (1931), audiences met a villain who didn’t charge or roar—he invited. Bela Lugosi’s Count Dracula spoke softly, moved deliberately, and embodied a new kind of cinematic terror: the fear of being controlled, consumed, and corrupted from within.

Just months later came Frankenstein, a film that permanently fused lightning storms and laboratory tables with the moral panic of unchecked creation. Boris Karloff’s Monster wasn’t evil—he was abandoned. And that distinction mattered. Universal horror wasn’t about monsters invading society; it was about society creating them.

This was radical storytelling for its time. The monsters weren’t external threats. They were reflections.

These Films Didn’t Just Scare Audiences — They Taught Hollywood How Genre Works

Universal’s early horror cycle did something no studio had systematized before: it turned genre into identity.

Audiences didn’t just go to see a movie—they went to see a Universal horror picture. That meant:

Expressionist shadows

Gothic sets that felt half-real, half-nightmare

Tragic figures doomed by fate, science, or desire

When The Mummy arrived, it blended romance, colonial guilt, and resurrection myths into a story about love that refuses to stay buried. When The Invisible Man hit screens, it turned scientific brilliance into madness, asking what happens when power arrives without accountability.

And by the time The Wolf Man emerged, Universal perfected the template of the tragic curse: a good man destroyed not by choice, but by inheritance. The monster wasn’t a villain—it was a diagnosis.

Hollywood took notes.

The Monsters Became Icons Because They Were Human First

What separated Universal’s monsters from cheap shocks was empathy.

These films asked audiences to sit with discomfort:

What if intelligence creates responsibility we can’t handle?

What if desire is dangerous?

What if the real horror is loneliness?

The makeup was iconic, yes. The performances unforgettable. But what made these characters immortal was that they weren’t monsters all the time. They were lonely. Angry. Romantic. Afraid.

That emotional core is why these characters survived parody, sequels, crossovers, wartime propaganda, Saturday matinees, and decades of imitation. They became shorthand for entire emotional states.

You didn’t need to see Dracula to know what Dracula meant.

Long Before “Universes,” Universal Built Mythology

Decades later, people would retroactively call this a “shared universe.” But Universal never marketed it that way.

The connections were loose, organic, almost accidental:

Actors crossed between roles

Monsters met in sequels

Continuity bent when it needed to

What mattered wasn’t coherence—it was mythic familiarity. Audiences returned not because of timelines, but because these figures felt timeless.

Universal didn’t ask, “How do these stories connect?”They asked, “What fear are we exploring this time?”

That question built a legacy no logo could replicate.

This Is Where the Story Begins

Before reboots, before modern franchises, before branding decks and cinematic roadmaps, there was a studio that understood something fundamental:

Monsters don’t endure because they’re powerful.They endure because they mean something.

The Universal Monsters weren’t designed to launch a universe.They were designed to haunt one.

And they still do.

ACT I: Hollywood Discovers Fear (And Universal Realizes It Can Sell It)

Before the monsters arrived, Hollywood itself was still figuring out what kind of creature it wanted to be.

In the late 1920s and early 1930s, the film industry was unstable, experimental, and—quietly—terrified. Sound had just crashed into cinema like a thunderclap. Silent film stars were vanishing overnight. The stock market had collapsed. Audiences wanted escapism, but they were also living inside a waking nightmare.

Enter Universal Pictures, a studio that, unlike its glossier rivals, didn’t have a monopoly on glamour.

Universal wasn’t MGM with its polish and prestige. It wasn’t Warner Bros. with its gangster grit. Universal was scrappier, riskier, and slightly off to the side of the industry’s power center—which turned out to be the perfect place to experiment with fear.

While other studios leaned into musicals and romances to distract audiences from reality, Universal leaned toward the anxiety.

Sound Changed Everything—and Horror Benefited the Most

When talking pictures arrived, studios panicked about dialogue. Universal saw an opportunity for atmosphere.

Sound meant:

Footsteps echoing down stone corridors

Doors creaking in the dark

Voices that could hypnotize instead of shout

Silence had once softened fear. Sound sharpened it.

Universal understood that horror didn’t need speed—it needed patience. Long pauses. Heavy accents. Words spoken slowly enough to crawl under your skin.

This realization directly shaped Dracula, whose terror came not from action, but from presence. Bela Lugosi’s Dracula didn’t rush. He lingered. He spoke like every sentence was a spell.

Audiences hadn’t seen anything like it. A villain who didn’t chase—he waited.

The Studio That Bet on the Uncomfortable

Universal’s monster era didn’t come from a single lightning-bolt decision. It was the result of a studio willing to adapt existing fear into cinematic form.

They looked to:

Gothic literature

European folklore

Stage plays that emphasized mood over motion

The visual language drew heavily from German Expressionism—distorted sets, aggressive shadows, exaggerated emotion—filtered through Hollywood craftsmanship. The result was a world that felt unreal but emotionally precise.

When Frankenstein followed Dracula later that same year, Universal confirmed it wasn’t dabbling—it was committing.

This wasn’t just another monster movie. It was a film about:

scientific arrogance

moral abandonment

and the terror of creating something you refuse to care for

The Monster wasn’t framed as a demon. He was framed as a mistake—ours.

That framing would become Universal’s secret weapon.

Monsters as Mirrors, Not Invaders

Most early genre films treated danger as something external: criminals, foreigners, disasters. Universal’s monsters turned the camera inward.

These stories asked:

What if progress goes too far?

What if desire corrupts?

What if loneliness becomes violence?

That’s why these films hit harder during the Depression. They weren’t escapism—they were recognition.

Audiences saw their fears reflected back at them:

Fear of unemployment → loss of identity

Fear of technology → uncontrollable creation

Fear of social change → corruption, transformation, decay

Universal horror didn’t reassure people that everything would be okay. It suggested that things might get worse—and that pretending otherwise was the real danger.

Universal Accidentally Invented the Horror Brand

By the early 1930s, something unexpected happened.

Audiences didn’t just recognize individual films—they recognized the vibe.

A Universal horror picture meant:

gothic sets

tragic monsters

moral consequences

and an unsettling emotional aftertaste

This consistency built trust. People came not just for scares, but for a specific feeling. Universal had done what no studio had formalized before: it turned horror into a recognizable brand without flattening it.

There was no “cinematic universe.” No master plan. Just repetition, refinement, and intuition.

Universal wasn’t chasing trends. It was defining a language.

Why This Moment Still Matters

This first act is why the Universal Monsters still exist in cultural memory nearly a century later.

They weren’t born from franchise logic.They were born from historical anxiety, technological change, and a studio willing to lean into discomfort instead of away from it.

Before monsters became IP, they were warnings. Before they became icons, they were questions.

And in the flickering light of early sound cinema, Universal figured out something Hollywood keeps relearning the hard way:

Fear doesn’t age. But formula does.

This was the soil the monsters grew from—and everything that followed, successful or not, traces back to this moment when movies first learned how to be afraid.

ACT II: The Golden Age of Monsters (When Horror Became Mythology)

Once Universal realized fear sold tickets, it did something far more impressive than repeating itself:

It evolved.

The early 1930s through the mid-1940s became the era when Universal’s monsters stopped being mere movie characters and started becoming modern myths. This was the moment when horror crystallized into archetypes—faces and stories so potent they’d survive parody, reinvention, and a century of cultural change.

And crucially, Universal did this without flattening its monsters into simple villains. Instead, it leaned harder into tragedy, psychology, and emotional consequence.

Frankenstein’s Monster Becomes the Template for Everything

If Dracula taught Hollywood how to fear seduction, Frankenstein taught it how to fear creation.

But it was Bride of Frankenstein that turned the Monster into something extraordinary: a character with an inner life.

James Whale’s sequel didn’t just continue the story—it interrogated it. The Monster learned to speak. He learned to hope. And then, devastatingly, he learned that companionship could still be denied to him.

This was radical. Horror sequels weren’t supposed to deepen themes. They weren’t supposed to be funny, self-aware, tragic, and philosophical all at once.

Yet Bride of Frankenstein did all of that—and in doing so, it quietly set a bar the genre is still chasing.

The Monster wasn’t scary because he killed.He was scary because he felt.

Universal Perfected the “Tragic Monster” Archetype

During this era, Universal refined its greatest invention: the monster as victim.

The Invisible Man wasn’t terrifying because invisibility is cool—it was terrifying because power without consequence breeds cruelty. Claude Rains’ disembodied voice became a symbol of unchecked ego.

The Mummy transformed resurrection into a love story haunted by imperial guilt and obsession.

The Wolf Man delivered the purest metaphor of all: masculinity, violence, and inherited trauma you cannot outrun.

Each monster represented a different human fear—but all shared one truth: the horror was internal.

Universal wasn’t asking audiences to fear the Other. It was asking them to fear themselves.

Makeup, Performance, and the Birth of Visual Iconography

This era also established something modern audiences take for granted: the look of monsters.

Jack Pierce’s makeup designs didn’t just disguise actors—they created symbols:

Frankenstein’s flat head and neck bolts

The Wolf Man’s gradual transformation

The Mummy’s decayed wrappings

These weren’t effects meant to impress. They were visual shorthand for emotional states—grief, rage, decay, loss of control.

Just as important were the performances. Boris Karloff, Lon Chaney Jr., Elsa Lanchester—these actors didn’t play monsters as threats. They played them as broken people trapped inside impossible bodies.

That choice is why these images remain instantly recognizable decades later. They weren’t designed to scare once. They were designed to linger.

Crossovers, Sequels, and the First Taste of Franchise Logic

As the Golden Age progressed, Universal began experimenting with sequels and monster crossovers—Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man, House of Dracula, House of Frankenstein.

In hindsight, these look like early franchise moves. At the time, they were pragmatic responses to audience demand.

The difference is intent.

These films didn’t exist to “expand lore.” They existed because audiences already loved the monsters. The studio followed affection, not strategy.

Continuity was loose. Canon was flexible. Tone varied wildly. And none of it mattered—because the emotional groundwork had already been laid.

People weren’t tracking timelines.They were revisiting characters.

War, Fatigue, and the End of Innocence

By the mid-1940s, the world had changed again.

World War II altered global consciousness. Real horror dwarfed cinematic horror. Universal’s monsters, once metaphors for anxiety, began to feel quaint against real-world devastation.

Budgets shrank. Scripts repeated. Parody crept in. By the time Abbott and Costello met Frankenstein, the Golden Age was effectively over.

But this wasn’t failure.

It was completion.

Universal had done something unprecedented: it had created a pantheon. These monsters were no longer just products of their era—they were templates future filmmakers would return to again and again.

Why Act II Is the Beating Heart of Universal Horror

This era is why the Universal Monsters still matter.

Not because they were scary by modern standards—but because they were honest.

They acknowledged:

fear as emotional

monstrosity as human

and horror as tragedy, not spectacle

Every successful reinvention of these characters—every good reboot, homage, or reinterpretation—draws from this period, whether it admits it or not.

This was the moment horror stopped being novelty and became myth.

And once something becomes myth, it never really dies.

ACT III: When the Monsters Stopped Scaring—and Started Surviving

Every mythology has a moment when belief fades.

For the Universal Monsters, that moment arrived not with a scream, but with a shrug.

By the mid-1940s, the Golden Age was ending—not because the monsters had failed, but because the world had changed faster than horror could keep up. Real atrocities had replaced metaphor. The shadows on screen no longer felt abstract; they felt familiar.

And when fear becomes reality, fiction has to adapt—or soften.

Universal chose survival.

When Real Horror Makes Movie Horror Feel Small

World War II didn’t just redraw borders. It rewired audiences.

After genocide, atomic bombs, and mass displacement, the idea of a lonely monster in a foggy village no longer carried the same weight. The Universal films hadn’t become worse—but the cultural context had become harsher.

Studios responded the only way Hollywood knows how: by making things lighter, faster, cheaper, and safer.

Budgets shrank. Shooting schedules tightened. Scripts reused old beats. The monsters remained—but their emotional depth slowly drained away.

Fear gave way to familiarity.

Enter the Crossovers: When Icons Become Mascots

Universal’s solution was logical, if creatively fatal: put the monsters together.

Films like Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man and later House of Frankenstein and House of Dracula treated the monsters less like tragic figures and more like recognizable pieces on a board.

This was the first time the monsters became content.

They weren’t introduced to explore new fears.They were reintroduced because audiences already knew them.

Continuity became a suggestion. Character arcs reset. Death stopped meaning much. The monsters could be revived endlessly, because now their job wasn’t to haunt—it was to appear.

And that shift changed everything.

Comedy Didn’t Kill the Monsters—It Preserved Them

Then came the moment many fans treat as sacrilege but history treats as inevitable:

Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein.

This film is often framed as the punchline—the moment Universal “gave up.” But that’s too simple.

Comedy didn’t mock the monsters into irrelevance. It canonized them.

By allowing Dracula, Frankenstein’s Monster, and the Wolf Man to exist in a comedic space, Universal acknowledged what they’d become: cultural fixtures. Safe enough to laugh at. Familiar enough to love.

Once a character can survive parody, it’s immortal.

The Last New Monster (And the End of an Era)

The final gasp of classic Universal horror came not from a castle, but from the water.

Creature from the Black Lagoon represented a pivot toward Cold War anxieties: science gone wrong, the fear of the unknown, the terror lurking beneath modernity.

The Creature was less gothic and more atomic. Less tragic romance, more evolutionary fear.

And then… silence.

Television rose. Drive-ins took over. Horror splintered into new forms—alien invasions, radioactive mutants, psychological thrillers. Universal’s original monsters didn’t vanish, but they stopped evolving.

They became legacy characters.

From Living Myths to Frozen Icons

By the late 1950s, the monsters no longer reflected current anxieties. They reflected nostalgia.

Universal responded by syndicating the films to television, unintentionally creating a new generation of fans—kids who watched these movies on weekend afternoons, absorbing the imagery without the original fear.

This is where the monsters transformed again:

from cinematic nightmares

to pop culture symbols

to Halloween costumes, lunchboxes, and late-night hosts

They were no longer owned by their era.They were owned by memory.

Why Act III Matters More Than It Seems

Act III is often treated as decline—but it’s really transition.

This is the phase where the Universal Monsters stopped being topical horror and became foundational mythology. They exited the present tense and entered the eternal one.

They didn’t need to scare anymore.They needed to endure.

And endure they did—through reruns, revivals, remakes, reinterpretations, and yes, misguided franchise attempts decades later.

You can only reboot something that never fully died.

The Lesson Hollywood Keeps Forgetting

Universal didn’t lose the monsters in Act III.

It lost the fear—and accidentally gained permanence.

By the time studios tried to resurrect these characters as blockbuster IP, they were no longer just movie villains. They were cultural heirlooms. Symbols that required care, perspective, and purpose.

Act III teaches the hardest lesson in franchise storytelling:

When characters stop evolving, they don’t disappear.They fossilize.

And fossils can be displayed, studied, and even admired—but bringing them back to life takes more than electricity and a logo.

It takes understanding why they mattered in the first place.

ACT IV: Resurrection Attempts (Or, How the Monsters Became Nostalgia Before They Became IP)

If Act III was about survival, Act IV is about confusion.

This is the long middle stretch—spanning decades—where the Universal Monsters never truly vanished, but also never fully returned. They drifted through pop culture like ghosts, endlessly resurrected but rarely understood, caught between reverence for the past and uncertainty about the future.

This was the era when Hollywood kept asking the same question in different fonts:

“Okay, but what do we do with these monsters now?”

Television Turned Nightmares Into After-School Companions

The first true resurrection didn’t happen in theaters. It happened on TV.

In the late 1950s and 1960s, Universal sold its monster catalog into television syndication. Suddenly, Dracula and Frankenstein weren’t forbidden midnight horrors—they were weekend programming.

Kids met these monsters out of order, without context, often censored, and usually sandwiched between commercials for cereal.

And something unexpected happened:the monsters became friendly.

Not harmless—but familiar. Comforting, even.

This generation didn’t fear the monsters. They bonded with them.

Which is wonderful for longevity—and disastrous for horror.

The Monsters Leave Universal…and Find New Blood Elsewhere

While Universal sat on its icons, other studios picked them up and ran.

Across the Atlantic, Hammer Film Productions injected new life into classic monsters with:

color

blood

sexuality

and postwar cynicism

Christopher Lee’s Dracula wasn’t tragic—he was predatory. Hammer understood something Universal hadn’t quite processed yet: monsters must reflect current anxieties or they become museum pieces.

Ironically, the most influential revivals of Universal’s monsters didn’t come from Universal at all.

That should have been a warning.

The Monsters Become Aesthetic, Not Allegory

By the 1970s and 1980s, the monsters were everywhere—but hollow.

They appeared in:

parodies

cartoons

novelty merch

Halloween specials

Their imagery survived, but their meaning didn’t.

Hollywood treated them like vintage posters you hang for vibes. Flat head. Cape. Claws. Done.

And when horror evolved—toward slashers, possession films, and psychological terror—the Universal Monsters stayed frozen in black-and-white elegance.

They were no longer scary.They were retro.

The 1999–2004 Window: When Universal Almost Cracked the Code

Then—briefly—it worked.

The Mummy wasn’t horror, but it understood tone. It treated the monster as a pulp myth, not a gothic tragedy, and leaned into adventure, romance, and charm.

Audiences loved it.

Universal followed with Van Helsing, which… tried to do everything at once.

This was the first modern warning sign. Van Helsing attempted:

multiple monsters

epic lore

franchise energy

Sound familiar?

It wasn’t that audiences rejected monsters. They rejected noise.

Nostalgia Becomes the Brand

By the 2000s, Universal increasingly leaned on the monsters as heritage, not narrative engines.

They were used to signal:

“classic Hollywood”

“prestige legacy”

“we own history”

But owning history isn’t the same as understanding it.

The monsters had become intellectual property in search of a thesis.

Universal knew these characters mattered. It just didn’t know why anymore.

Act IV’s Quiet Tragedy

This era wasn’t a failure of execution—it was a failure of interpretation.

Universal spent decades circling its monsters, afraid to break them, afraid to modernize them too much, afraid to let them mean something new.

So they hovered in limbo:

too iconic to discard

too undefined to evolve

And that hesitation set the stage for what came next—the loudest, most expensive resurrection attempt of all.

Act IV ends not with a scream, but with a corporate realization:

“If nostalgia isn’t enough… maybe a universe will be.”

And that thought leads directly into the final act—where everything old was about to be branded, interconnected, and spectacularly misunderstood.

ACT V: The Dark Universe (Or, How Universal Tried to Speedrun 100 Years of Mythology)

If Act IV ended with a dangerous thought, Act V begins with a disastrous sentence:

“What if we made our own MCU?”

Thus, in the mid-2010s, Universal Pictures made the boldest mistake in modern franchise history: it confused longevity with inevitability.

The Universal Monsters had survived a century. Surely audiences would show up automatically—right?

Right?

Step One: Announce the Universe Before Anyone Asked

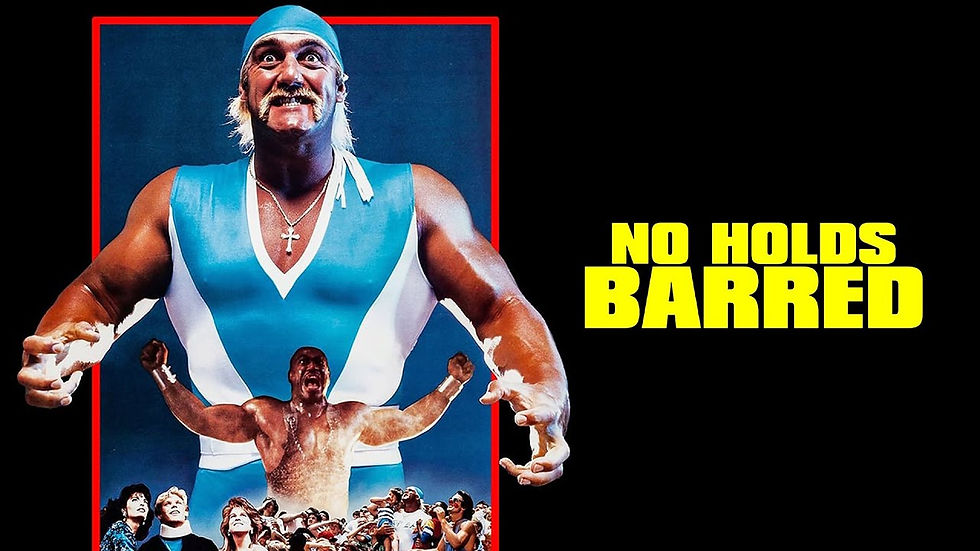

In 2017, Universal officially unveiled the Dark Universe—complete with:

a dramatic logo

a Danny Elfman theme

and a now-infamous cast photo featuring A-listers posed like they’d just joined a very serious LinkedIn group

This announcement happened before the first movie even premiered.

This is the franchise equivalent of sending wedding invitations before the first date.

Marvel built goodwill one hit at a time. Universal tried to manifest confidence through branding, hoping audiences would mistake preparation for proof.

They did not.

Step Two: Make The Mummy Do Franchise Labor

The launchpad was The Mummy, a movie tasked with:

reintroducing a classic monster

modernizing horror

launching a shared universe

teasing future characters

and functioning as a Tom Cruise action vehicle

That’s not a screenplay. That’s a hostage situation.

The film couldn’t decide what it was:

horror? barely

adventure? sometimes

mythology lesson? constantly

Every time the story slowed down, the movie panicked and shouted “LORE!”—usually through Dr. Henry Jekyll, who existed primarily to explain future movies that were never made.

Audiences felt the strain. Critics smelled the setup. And the box office response landed in the most dangerous zone of all: expensive but unloved.

Step Three: Mistake Star Power for a Creative Vision

Universal’s strategy leaned heavily on celebrities:

Tom Cruise as the anchor

Russell Crowe as franchise glue

public plans involving Johnny Depp and Javier Bardem

The logic was simple: big stars = instant legitimacy.

But monsters don’t need legitimacy.They need meaning.

The Dark Universe treated monsters as IP roles rather than metaphors. Dracula wasn’t about desire. Frankenstein wasn’t about creation. The Wolf Man wasn’t about loss of control.

They were future content nodes.

And that’s the problem: monsters don’t survive being managed.

Step Four: Forget That Monsters Aren’t Superheroes

The Dark Universe’s biggest misunderstanding was structural.

Marvel heroes work because:

they choose their powers

they form alliances

they protect society

Universal monsters are the opposite:

they’re cursed

they’re isolated

they’re feared, hunted, or destroyed

They don’t assemble.They collide.

Trying to turn them into a proactive team was like forcing Greek tragedies into a group chat.

The monsters didn’t need connectivity. They needed specificity.

Step Five: Panic, Retreat, Collapse

Once The Mummy failed to ignite enthusiasm, everything unraveled at record speed:

creative leads exited

Bride of Frankenstein halted mid-prep

release dates vanished

the “universe” quietly stopped existing

This wasn’t a slow fade. It was an emergency brake.

Shared universes thrive on confidence. The moment Universal hesitated, the illusion shattered.

The Dark Universe didn’t die because audiences rejected monsters. It died because audiences rejected being sold a roadmap instead of a movie.

The Cruel Irony: Universal Solved the Problem Immediately After

Almost immediately after the collapse, Universal pivoted—and accidentally proved why the Dark Universe was doomed.

Instead of connectivity, it embraced:

standalone films

filmmaker-driven visions

smaller budgets

The result? The Invisible Man, a sharp, modern reinterpretation that worked because it had:

a clear theme

emotional focus

and zero interest in launching anything

It didn’t promise a universe. It delivered a story.

Why Act V Was Inevitable—but Not Necessary

The Dark Universe wasn’t an out-of-nowhere failure. It was the logical endpoint of decades of misunderstanding.

Universal spent so long treating its monsters as icons that it forgot how to treat them as characters.

Act V teaches the most painful lesson of all:

You cannot franchise meaning. You must earn it—one story at a time.

The monsters were never broken.The strategy was.

And with that realization, the story finally turns toward something quieter, smarter, and—ironically—much closer to where it all began.

ACT VI: After the Universe (When Universal Remembered How Monsters Actually Work)

After the Dark Universe collapsed, something rare happened in modern Hollywood:

Universal stopped talking.

No splashy announcements. No logos. No “Phase One.” Just a quiet, slightly embarrassed pivot away from the wreckage—like a studio sneaking out of a party it definitely bragged about hosting.

And in that silence, Universal finally remembered the lesson it had already learned once, nearly a century ago:

Monsters don’t need a universe.They need a reason to exist right now.

Smaller Movies, Sharper Teeth

The turning point came not with a rebrand, but with a single, focused film:

The Invisible Man.

No crossover bait. No franchise teases. No dramatic cast photo.

Instead, the film reinterpreted invisibility as:

domestic abuse

surveillance

gaslighting

and the terror of not being believed

The monster wasn’t a gothic figure in a castle.He was modern, intimate, and plausibly real.

And audiences responded.

This wasn’t nostalgia. This was relevance.

Horror Didn’t Need Blockbuster Budgets—It Needed Perspective

Universal’s quiet alliance with Blumhouse Productions signaled a philosophical shift.

Blumhouse’s model—low-to-mid budgets, filmmaker autonomy, and concept-first storytelling—aligned perfectly with what the Universal Monsters had always done best.

Fear thrives when:

stakes are personal

settings are contained

ideas are sharp

You don’t need $200 million to feel dread. You need a premise that crawls under the audience’s skin and refuses to leave.

This was Universal accidentally circling back to its own DNA.

The Monsters Return—Individually

Post–Dark Universe, Universal stopped asking “How do these characters connect?” and started asking “What does this monster mean now?”

That shift matters.

A modern Wolf Man doesn’t need to fight Dracula.He needs to explore:

inherited trauma

masculinity

loss of control in a world obsessed with dominance

A modern Frankenstein story doesn’t need lore. It needs to confront:

artificial intelligence

creator responsibility

abandonment on a technological scale

By isolating the monsters again, Universal restored their power.

The Funniest Twist: The Dark Universe Works… As a Theme Park

In perhaps the most poetic irony of the entire saga, the “Dark Universe” name didn’t vanish.

It was reborn as a land inside Universal Epic Universe—a place where interconnected branding actually makes sense.

Theme parks thrive on:

recognizable icons

shared spaces

modular storytelling

Movies don’t.

Universal finally put the concept where it belonged.

The monsters weren’t humiliated by this move. They were liberated.

Legacy vs. Living Myth

Act VI is about choosing between two versions of immortality.

One version freezes characters in amber:

logos

brand recognition

reverence without reinvention

The other lets them change—even risk alienating audiences—by letting them reflect new fears.

Universal Monsters only survive when they’re allowed to be alive.

Not coordinated.Not optimized.Not synergized.

Alive.

Where the Story Leaves Us

Universal now stands where it stood in the early 1930s:

at a cultural crossroads

with powerful symbols

and a choice about how to use them

The monsters don’t need saving.They need listening.

Because every era invents its own fears—and monsters only matter when they speak that language fluently.

Act VI doesn’t promise a grand return. It promises something better:

A chance to let the monsters be scary again.

Not because they’re iconic.But because they’re honest.

And if Universal remembers that, it won’t need another universe.

It will just need a good story.

EPILOGUE: Monsters Don’t Die — They Wait (And What Universal Must Do to Earn Them Back)

The full history of the Universal Monsters reads less like a straight line and more like a heartbeat.

Creation.Growth.Decay.Resurrection.Collapse.Silence.

And now—possibility.

From the early days of sound cinema to the corporate overreach of the Dark Universe, Universal Pictures has repeatedly learned (and unlearned) the same lesson: monsters only matter when they reflect the fears of the moment with sincerity.

Every time Universal forgot that, the monsters became mascots.Every time it remembered, they became immortal again.

The Full Arc, in One Sentence Per Era

Act I (1930s): Monsters are born from anxiety and technological change.

Act II (1930s–40s): Monsters become myth through empathy and tragedy.

Act III (1940s–50s): Monsters stop evolving and fossilize into icons.

Act IV (1960s–2000s): Monsters become nostalgia, then IP without a thesis.

Act V (2017): Monsters are mistaken for inevitability and collapse under branding.

Act VI (2020s): Monsters quietly return when treated as stories again.

This isn’t a failure curve. It’s a warning loop.

Why the Dark Universe Was Inevitable — But Also Avoidable

The Dark Universe didn’t come from nowhere. It was the end result of decades of hesitation.

Universal knew:

the monsters mattered

audiences recognized them

the IP had value

What it didn’t know anymore was what they were for.

So the studio did what modern Hollywood does under uncertainty: it copied the most successful template available and hoped legacy would fill in the gaps.

But monsters aren’t superheroes.They don’t scale horizontally.They don’t benefit from sameness.And they absolutely do not thrive under optimization.

The Dark Universe failed not because it was ambitious, but because it was conceptually empty.

The Real Problem: Universal Confused Ownership With Understanding

Owning the monsters is not the same as understanding them.

Universal treated its characters as:

brand anchors

content generators

interconnected assets

But historically, the monsters only worked when they were treated as:

metaphors

tragedies

cautionary tales

Frankenstein is about responsibility.Dracula is about desire and control.The Wolf Man is about inherited violence.The Invisible Man is about power and belief.

These meanings are not optional flavor.They are the entire point.

Strip them away, and you’re left with costumes.

How Universal Can Actually Course-Correct (For Real This Time)

Here’s the uncomfortable truth: Universal already has the solution. It just needs the discipline to commit to it.

1. No More “Universe” Language

Never say it again. Not internally. Not publicly. Not as a wink.

If connections happen organically in twenty years, great.But planning them upfront poisons the well.

Shared mythology is an outcome, not a goal.

2. One Monster = One Idea

Every monster project should answer one question clearly:

“What modern fear does this story explore?”

Not five fears.Not a lore roadmap. One sharp, contemporary anxiety.

If the pitch doesn’t fit on a napkin, it’s wrong.

3. Budget Like Horror, Not Spectacle

Horror thrives under constraint.

Lower budgets:

force specificity

protect risk-taking

reduce panic when box office is merely “good”

Universal’s monsters should live in the $20–60M range, not the $200M danger zone.

Fear is intimate. Spend accordingly.

4. Hire Filmmakers With POV, Not Franchise Experience

The most successful modern horror films come from directors with something to say, not something to manage.

Universal doesn’t need architects. It needs authors.

Let each monster belong to a different voice, tone, and style—even if they clash.

Especially if they clash.

5. Let Some Films Fail

This is critical.

The original Universal Monsters weren’t all hits. Some were messy. Some were odd. Some aged poorly.

That’s fine.

A mythology built on perfection is brittle.A mythology built on risk endures.

The Inevitable Question: Will Universal Try Again?

Yes. Of course it will.

The monsters are too valuable, too embedded, too resonant to stay dormant forever. But the next attempt doesn’t need to be louder.

It needs to be smarter.

If Universal treats these characters not as legacy obligations but as living metaphors—capable of evolving with the culture rather than branding it—the monsters don’t just survive.

They thrive.

The Final Irony

Universal didn’t invent monsters.

It invented modern monsters—creatures that reflect society’s anxieties back at itself with empathy, tragedy, and restraint.

That legacy was never broken. It was just misunderstood.

And monsters are patient.

They can wait decades in the dark for the right moment, the right voice, the right fear.

All Universal has to do now is stop trying to control them—

—and let them speak again.

Comments