1990: The Bronx Warriors — A Leather-Clad Disasterpiece We Can’t Stop Loving

- Dec 21, 2025

- 20 min read

(A Super-Deep, Super-Silly Pop Culture Blog Review)

If cinema were a thrift store, 1990: The Bronx Warriors would be that astonishing jacket you know you shouldn’t wear in public—but still try on “just for fun”—and then suddenly you’re wearing it everywhere and telling people it’s “vintage.” The film is a beautiful, rusted-out dumpster fire of Italian exploitation ambition, New York nihilism, and possibly the world’s largest supply of fake smoke.

Strap on your studded leather and roller skates. We’re going in.

THE APOCALYPSE… MADE IN ROME

(or: Italy Decides to Make New York Edgier)

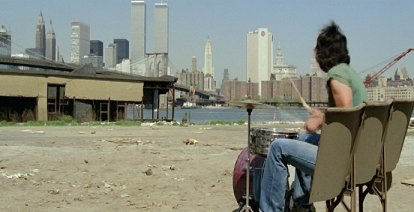

You might think this movie was filmed in gritty, dangerous, early-80s NYC. And technically, parts were—just long enough to grab some exteriors that scream “abandoned industrial hellscape.”

But the rest? Absolutely shot in Rome, where production designer types did their best to replicate “the Bronx” using:

Italian warehouses

European storefronts

A seemingly endless fog machine budget

Extras who look a little too healthy for the apocalypse

If New York was the inspiration, Italy was the interpretation. And the interpretation was:

“Urban decay… but make it fashion.”

The director, Enzo G. Castellari, was king of the Italian knockoff genre—he didn’t just imitate Hollywood trends; he multiplied them. When The Warriors, Escape from New York, and Mad Max 2 hit, Castellari said, “Yes. All of that. At the same time.”

The result? A movie that feels like a birthday card written by someone who skimmed the Wikipedia article for New York.

PLOT BREAKDOWN: GANGS, CORPORATE WARS & HAIR GEL

(aka: The Bronx Is Closed, Please Leave a Message)

Let’s walk through the madness in all its beat-by-beat glory.

ACT I – Welcome to the Bronx, Population: Leather

The year is 1990, aka the future, which is signaled by:

smoke

graffiti

people wearing more straps than clothing

The U.S. government has written off the Bronx as a no-go zone, meaning gangs rule everything and the police show up only to collect paychecks and trauma.

Enter Ann, a 17-year-old runaway heiress to the evil mega-corporation The Manhattan Corporation, which makes weapons and bad decisions. She flees into the Bronx because she doesn’t want to inherit a global killing machine. This may be the most relatable character motivation ever written.

She’s immediately attacked by the Zombies, a roller-skating gang that proves Italians should never be allowed to design American subcultures. Ann is rescued by Trash, leader of the Riders, a biker gang with a strict dress code (leather only).

Trash speaks very little, which is wise because every time he does, he sounds like he’s reading off a cue card just out of frame.

ACT II – Corporate Shenanigans & Gang Diplomacy

The Manhattan Corporation sends in Hammer, a mercenary who looks like the only cast member who actually read the script. His mission: retrieve Ann, by any amount of murder necessary.

Hammer’s plan?

Sneak into the Bronx.

Bribe the gangs.

Cause chaos.

Sneer a lot.

Meanwhile, Trash visits The Ogre, leader of the Tigers, who live in a fabulous art-deco theatre and dress like post-apocalyptic royalty. Ogre’s wardrobe alone deserves its own box set.

Alliances are forged. Backstabbing soon follows, because this is the Bronx and trust has been outlawed since 1985.

ACT III – All-Out War, Lots of Smoke, Zero Subtlety

Hammer manipulates the Riders into internal conflict, then unleashes a corporate death squad on the Bronx. Ann is captured, held hostage, and ultimately killed in a shootout—ending her hopeful attempt at self-liberation.

Trash and Ogre team up to take down Hammer in a grand finale full of:

slow-motion bullets

dramatic tumbles

bikes crashing through things that should not be crashed through

Trash kills Hammer… but at what cost?(Hint: Everyone is dead. The cost was everyone.)

Fade to black. Roll credits. Find nearest leather vest.

CINEMATOGRAPHY: SMOKE, SHADOWS & “IS THIS A ROCK VIDEO?”

(The Bronx Has Never Looked So Roman or So Cinematically Sweaty)

If 1990: The Bronx Warriors had nothing else going for it — no plot, no characters, no functioning microphones — it would still be a joy to watch thanks to the cinematography of Sergio Salvati, a legend of Italian genre film who somehow made a post-apocalyptic Bronx look like a cross between a western frontier town, a heavy metal music video, and a fever dream filmed inside an abandoned steel mill.

The visuals are lush, gritty, and mythic all at once. They give the movie a sense of scope and atmosphere that its budget had no right to support. Salvati basically said:

“Fine, we don’t have money.But we do have sunlight and smoke machines. Watch me work.”

1. The Look of the Bronx: A Myth, Not a Location

The film’s version of the Bronx is not remotely realistic — and that’s the point. Salvati shoots New York as if it’s a post-industrial wasteland caught in eternal golden hour. When the production moved to Italy for interiors and controlled shots, he kept the same palette, giving the entire film a cohesive dreamlike tone.

Key characteristics:

Dusty, sun-drenched exteriors that make everything feel scorched.

Thick layers of smoke that hide the seams of cheap sets and add atmosphere.

Wide-angle compositions that make empty streets look epic rather than underpopulated.

Harsh, directional lighting that turns shadows into jagged shapes.

The Bronx functions more as a symbolic landscape:a lawless, abandoned frontier where the ruins feel poetic rather than depressing.

2. Smoke Machines: The True Uncredited Cinematographer

The smoke in this movie is so omnipresent it deserves its own SAG card.

Salvati uses smoke to:

add texture,

obscure limitations,

silhouette characters,

hide the fact that a “New York alley” is actually a Rome warehouse,

make even a simple shot of a guy standing still look like a metal album cover.

If you thought fog was a mood in Escape from New York, prepare to see fog treated like a lead character.

3. Slow Motion Shots: Violence as Opera

Italian action cinema of the 70s and 80s worshipped slow motion, but Bronx Warriors treats it like a religious experience. Salvati and director Castellari had worked together on several action films and were masters of making cheap stunts look mythic.

Slow motion is used for:

bike crashes

bodies flying through windows

dramatic death spirals

heroic leaps

emotionally charged head turns (yes, even those)

Every major stunt gets the “let’s admire this” treatment, giving the film a sense of grandeur built on the backs of stunt performers who almost certainly did not sign enough safety waivers.

4. Color Palette: Industrial Sunset Glamour

The film is shot in rich tones that evoke:

rust,

gunmetal,

embers,

sunset gold,

and the occasional splash of neon from gang costumes.

Nothing looks clean. Everything looks lived-in, burnt, or coated in a thin layer of stylish filth.

It’s dirty, but beautifully dirty. Like a painter choosing grimness as a theme.

5. Lens Choices: Wides for Myth, Close-Ups for Chaos

Salvati balances two modes:

Wide-Angle Epicness

Used for:

establishing the Bronx as abandoned frontier

revealing the scale of biker gangs

shooting empty warehouses like they’re Roman ruins

The wides make the gangs feel like armies rather than groups of Italians in mismatched leather.

Tight Close-Ups

Used aggressively in:

fights,

arguments,

tense standoffs,

character introductions,

scenes where the director wants you to feel the sweat.

These close-ups are less about intimacy and more about raw attitude.Trash’s entire performance style benefits from the hero lighting and heroic framing.

6. Camera Movement: A Dance Between Controlled and Chaotic

The film’s camera movements walk a fine line between cinematic precision and the “run and gun” spirit of exploitation filming.

Controlled movements include:

slow dolly shots into character faces

elegant pans revealing gang hideouts

tracking shots following motorcycles

Chaotic movements include:

handheld shakes during fights

sudden whip-pans

reaction shots that feel like the camera operator was surprised too

This blend keeps the film’s energy high and unpredictable—perfect for a world on the brink of collapse.

7. Night Scenes: The Bronx After Dark (AKA “Add More Smoke”)

Night scenes aren’t just dark — they’re stylized:

silhouettes lit from behind

burning barrels everywhere

deep shadows concealing half-built sets

occasional blue gels to add that sweet 80s neon dystopia vibe

The darkness feels alive and dangerous, like the Bronx is breathing smoke and glowing from within.

8. Industrial Aesthetic: Factory Chic Before It Was Cool

Salvati shoots abandoned factories, crumbling piers, tunnels, and rusted shipping yards like they’re temples of a fallen civilization.

Every location looks like it was chosen specifically for:

texture

atmosphere

decay

the cinematic joy of riding a motorcycle through it at unsafe speeds

The Bronx becomes less a place and more a post-apocalyptic fashion runway.

9. Visual Storytelling: Meaning in the Mayhem

Despite the low budget, the cinematography sneakily provides world-building:

Gangs are framed like tribes in old epics.

Battles are staged like miniature wars.

The Ogre’s headquarters is lit like royalty.

Trash is always centered in frame — even in chaos — reinforcing his mythic status.

Corporate scenes are sterile and overlit, contrasting the warm, dirty Bronx.

The movie understands that audiences will forgive narrative holes if the images are strong enough. And they are.

THE SCORE: SYNTHS, GUITARS & THE SOUND OF SWEAT

(Walter Rizzati’s Magnum Opus of Post-Apocalyptic Excess)

If 1990: The Bronx Warriors had no plot, no actors, and no working lights, it would still be worth watching for its absolutely unhinged, totally committed, fist-pumping score by composer Walter Rizzati. This soundtrack doesn’t accompany the movie; it attacks it. It’s the kind of music that kicks down your door on a motorcycle, steals your stereo, and still expects you to thank it.

Rizzati’s work sits at the intersection of:

John Carpenter synth minimalism (if Carpenter drank three espressos too many),

Italian prog-rock pomp,

and arena-metal drama, all wrapped in that warm analog hum that only 1980s tape machines can provide.

It’s the aural equivalent of a leather vest.

1. The Rhythm Section: Drums That Think They’re the Main Character

The drum programming in this score does not believe in subtlety. It’s all:

pounding toms,

galloping rock beats,

and snare hits that sound like someone slapping a frying pan for justice.

The rhythm section is mixed loud, often louder than the dialogue, which honestly improves the film. Who needs to hear Trash mumble when you can hear a snare drum declaring war on your eardrums?

These beats don’t just underscore action scenes—they drag the film into action even when nothing is happening. A character will stare intensely, and the drums jump in like:

“OH, IT’S ON NOW.”

2. Guitars of Doom: Melodic, Melodramatic, and Magnificently Over-the-Top

The electric guitar parts are pure exploitation cinema bliss: big bends, crunchy chords, and solos so melodramatic they could be auditioning for a glam-metal opera.

These riffs don’t just underscore the gangs—they become the gangs:

The Riders get searing biker-rock lines.

The Tigers’ scenes glow with funkier, swagger-infused riffs.

The corporate goons are greeted with colder, more mechanical guitar textures.

Every strum feels like it’s wearing sunglasses indoors.

3. Synths: The Neon Glue That Holds the Bronx Together

This is where the score truly shines.

Rizzati’s synth work is a neon, pulsing, sometimes weirdly romantic undercurrent that gives the Bronx its mythic, dystopian heartbeat. The synths are always doing something interesting:

Drone beds that make empty streets feel ominous and endless.

Arpeggiated pulses that create tension even when the plot refuses to.

Lush pads that add melancholy to scenes that would otherwise be two actors staring into the middle distance.

The synth sound is so rich you can practically taste the analog circuitry.

4. Leitmotifs: More Character Than the Actual Characters

Trash may not have much in the way of emotional range, but his musical theme sure does. The score gives different factions and moments their own recognizable motifs.

Trash’s music = brooding biker melancholy.

The Ogre’s music = confident, regal funk-rock.

Hammer’s theme = mechanical menace with synth stabs sharp enough to cut steel.

The music paints more emotional depth than the script ever attempts. In a way, the score is the film’s unofficial narrator.

5. Mixing & Presence: “Turn It Up, They Won’t Notice the Budget”

The sound mix gives the score pride of place:front and center, unapologetically loud, often overpowering:

explosions,

dialogue,

ambient noise,

and basic logic.

This is not a bug; it’s a feature.

When the budget starts to show—cheap props, awkward staging, Mark Gregory trying to act—the score swoops in like a heroic leather angel to cover the seams.

The filmmakers clearly knew what their strongest asset was, and they leaned so far into it they fell through the floor.

6. Legacy: A Soundtrack That Earned Its Cult Status

Within exploitation cinema circles, Bronx Warriors is often remembered more for its music than its plot. The soundtrack has been released, reissued, ripped, remixed, and used in fan edits and homage videos. It’s one of those rare low-budget scores that transcends its origins.

You could play it for someone who’s never seen the movie and they’d still say:

“This absolutely slaps.”

It’s not just good “for a low-budget film.”It’s good, period.

The score elevates the movie far beyond what its ragtag production ever should have allowed.

EDITING: CHAOTIC GOOD CINEMA

(Or: How to Cut a Movie With Scissors, Coffee, and Sheer Confidence)

The editing of 1990: The Bronx Warriors is not just a technical component — it’s a full-blown personality. A chaotic, hyperactive, slightly unhinged personality, but a personality nonetheless. Watching the film feels like sitting next to someone who keeps fast-forwarding and rewinding during an action scene, insisting, “No, wait, this is the good part!”

The editor (the legendary Vincenzo Tomassi) seems to have approached the task with three guiding principles:

Momentum is more important than logic.

Slow motion can solve any problem.

If in doubt, cut to someone falling off something.

And honestly? It works.

1. Action Editing: A Ballet of Mayhem and Questionable OSHA Compliance

The action sequences are constructed like grindhouse poetry:

Bikers crash through glass in slow motion,

people tumble off rooftops,

explosions happen 10 feet behind the actors and everyone pretends it’s normal,

objects are thrown at camera like the editor wanted to startle the audience awake.

Most scenes don’t follow traditional spatial continuity, but they do follow what I can only describe as emotional continuity. You feel like the action is coherent even if you couldn’t draw a map of what’s actually happening.

The result is visceral, often hilarious, and always entertaining.

2. Slow Motion: The Movie’s Love Language

You cannot talk about the editing without addressing the elephant in the room:THE SLOW MOTION. So much slow motion. All of the slow motion. Every last drop of slow motion in Italy circa 1982, poured lovingly into this film.

Why is that biker leaping off his motorcycle in slow-mo?Why is someone falling gently sideways like they slipped on a banana peel but dramatically?Why is Trash turning his head like an 80s shampoo commercial?

Because slow motion adds:

drama,

weight,

time to pad out the runtime.

Slow-mo becomes an editing tool for stretching small stunts into cinematic glory.

It’s both ridiculous and glorious — like if Sam Peckinpah and a metal band collaborated on a student film.

3. Scene Transitions: Abrupt, Confident, and Fully Uninterested in Your Feelings

This movie LOVES a smash cut.

And not just any smash cut.I’m talking about cuts that feel like the editor stood up and shouted:“Enough of THAT! NEXT SCENE!”

Examples of sudden transitions include:

emotional moments cut short by explosions,

conversations ending mid-thought to introduce new gangs,

fights that start mid-swing because the editor clearly felt the preamble was wasting everyone’s time.

There’s a real punk-rock confidence to it:why linger when you can yank the viewer into the next high-energy beat?

4. Narrative Structure: The Plot Wanders, The Editing Drags It Back

Let’s be honest: the script is… adventurous.The plot sometimes:

loses track of characters,

forgets motivations,

introduces ideas but refuses to follow through,

kills characters before you remember their names.

But the editing does its best to paper over these structural quirks by:

cutting faster during confusing scenes,

building sequences around mood instead of exposition,

skipping unnecessary connective tissue entirely (“Why are we HERE now?” “Shh. ACTION.”)

And bizarrely, this helps the film. It creates an energy that feels more mythic than realistic, like the Bronx is less a place and more a fever dream stitched together by vibes.

5. Editing as Misdirection: The Budget Is Low, But the Cuts Are Furious

Whenever the production values start to show (and boy, do they show), the editor responds with:

quick cuts,

close-ups,

shaking the frame,

or throwing in some strobing lights.

You’ll see something cheap or awkward for half a second — then WHOOSH, new angle. It’s like the editor is whispering, “Don’t look too close at that, look at THIS instead!”

It’s the cinematic version of sweeping dirt under a rug but doing it fast enough that nobody notices.

6. Audio Editing: Let the Music Do the Heavy Lifting

The sound editing and score integration are aggressive in the best way possible.Whenever a scene starts sagging, the soundtrack kicks the door open like a biker entering a saloon:

Synths blast.

Guitars wail.

Drums remind you that you’re supposed to be pumped.

The audio transitions aren’t subtle — they’re motivational speeches disguised as music cues.

7. Editing as Attitude: The Bronx, But Make It Stylized

The editing injects a sense of stylization that the production design can’t always fully match. By cutting sharply, bending time with slow-mo, and keeping scenes moving at breakneck speed, the film achieves a hyperreal comic-book texture.

The Bronx becomes not just a location, but a rhythm — a pulse — a chaotic montage of desperation and bravado held together by scissors and bravado.

CAST BREAKDOWN: A MIX OF ICONS & PEOPLE WHO WERE JUST THERE

(Everyone Acts Like They’re in a Different Movie — And That’s the Magic)

The cast of 1990: The Bronx Warriors is a chaotic ensemble of trained actors, action icons, Italian newcomers, and guys who probably thought they were showing up for a motorcycle commercial. Each performer brings their own energy, their own level of commitment, and often their own hairstyle budget.

The result is a cast where half the people are underacting, half are overacting, and Fred Williamson is doing exactly the right amount of acting. Let’s dive into the glorious madness.

TRASH (Mark Gregory)

The Silent Biker Hero Who Works Out More Than He Talks

Mark Gregory is not a traditional actor; he is a posture artist. Critics have said he poses more than he performs, but that’s part of the charm. Picture someone too pretty to be intimidating, too innocent to be a gang leader, yet somehow too cool to ignore. That’s Trash.

Key Traits:

Always stands with his hips slightly forward, like he’s continually trying to sell jeans.

Has the emotional range of a stoic action figure.

Speaks as if every line is being fed to him through a hidden earpiece.

Looks like he’d lose a fight to a gust of wind, but wins because the soundtrack insists he’s a badass.

But here’s the thing: Gregory has presence. It’s strange, vulnerable, almost mythic. He feels like someone who wandered out of a fantasy novel and onto a motorcycle.

Trash works not because of his acting, but because of his whole… Trashness. He’s the ultimate Italo-action protagonist: handsome, mysterious, and filmed like he’s the centerfold of a dystopian teen magazine.

THE OGRE (Fred Williamson)

The Actual Star of the Movie, Whether the Movie Knows It or Not

Every time Fred Williamson enters the frame, the film improves by at least 40%. He carries the swagger of a man who refuses to lose, in movies or in life. His character, The Ogre, rules the Tigers with:

regal calm,

gold-trimmed capes,

an art deco hideout,

and the vibe of a retired boxer turned post-apocalyptic king.

Williamson’s performance is cool without effort — the kind of cool that comes from being absolutely certain you can beat up everyone in the room without adjusting your collar.

He brings gravitas, confidence, and a bit of sly humor, grounding the chaotic energy of the film with pure charisma. If the whole movie had been about The Ogre, we might be talking about this film as a cult masterpiece rather than cult trash.

HAMMER (Vic Morrow)

The Only Man Taking This Seriously — Which Makes It Hilarious

Vic Morrow plays Hammer like he wandered in from a gritty 70s cop thriller and refused to change genres. He’s intense, vicious, and clearly exhausted by every other character’s nonsense.

Notable Hammer qualities:

Looks perpetually irritated, like he’s stuck in line at the DMV behind a guy wearing roller-skate armor.

Underplays everything, which weirdly makes him scarier.

Performs unlike anyone else in the movie — like he’s in an Oscar drama while everyone else is in a glam-metal music video.

Hammer adds necessary darkness to the film. His scenes feel like someone turned off the neon lights and turned on a single flickering bulb in a basement.

ANN (Stefania Girolami)

The Symbolic Heart of the Bronx — With Too Few Lines

Ann is the story’s inciting spark: a 17-year-old heiress fleeing corporate tyranny by running straight into gangland. She’s soft-spoken, gentle, and idealistic — a contrast to the gritty world around her.

But the script doesn’t give her nearly enough to do. She spends much of the film:

being rescued,

being kidnapped,

being threatened,

being saved again.

Still, Girolami infuses Ann with a sincerity the film badly needs. Her presence gives Trash a reason to fight and gives the Bronx something pure to rally around.

Her tragic death is one of the few genuinely emotional beats, and Girolami sells it with far more nuance than the movie earns.

ICE (Giancarlo Prete)

Trash’s Second-in-Command With the World’s Worst Loyalty Record

Ice is the Riders’ number two, a man whose loyalty is questionable from the moment we meet him. His arc is pure Shakespearean betrayal, if Shakespeare had written exclusively for late-night cable.

Ice brings:

a sweaty, jittery intensity,

eyes that look guilty even before he’s done anything wrong,

a vibe that screams “I am absolutely going to sell you out, please don’t ask me why.”

His performance is campy but committed, and his final betrayal is one of the film’s dramatic high points.

HOT DOG (Christopher Connelly)

The Veteran Gang Leader Who Knows He’s in a Movie

Hot Dog is one of the Riders’ elder statesmen — a man who looks like he’s been in the Bronx since Nixon. Christopher Connelly plays him with a mischievous charm, as if he’s constantly on the verge of winking at the camera.

He brings:

levity,

experience,

excellent 80s stubble,

and the energy of someone who has absolutely seen it all.

Hot Dog’s banter gives the Riders a lived-in feel, making them more than just leather mannequins in slow motion.

WITCH (Betty Dessy)

Glam-Punk Oracle and Bronx Icon

Witch appears only briefly, but oh boy does she leave a mark.

She’s the leader of a mysterious, quasi-magical gang of dancers/warriors who seem to live in a funhouse built out of smoke machines and broken mirrors. She’s basically:

a goth prophecy queen,

a glam-rock sorceress,

and an art-school installation piece that learned martial arts.

Her scenes add surreal texture to the Bronx, like someone dropped a Grace Jones music video into the middle of a biker flick.

THE ZOMBIES (Led by uncredited skating maniacs)

Roller-Skate Death Squad Supreme

The Zombies aren’t so much characters as they are a concept, and that concept is:

roller skates,

hockey pads,

undead makeup,

and the ability to kill while doing sick spins.

Are they practical? No.Are they terrifying? Also no.Are they unforgettable? Absolutely.

They embody everything brilliant about this film: ridiculous, stylish, and utterly unbothered by realism.

THE TIGERS (The Ogre’s Army of Fashion-Forward Badasses)

Rhythm, Style, and Orange Satin

The Tigers are the Bronx by way of a funk concert. They dress in matching orange satin, carry spears like they’re extras in a disco-themed Ben-Hur, and move with synchronized swagger.

Individually, they aren’t fleshed out. Collectively, they’re the coolest gang in the film. They feel like a society with rituals and structure, thanks to Williamson’s leadership and their theatrical presentation.

THE MANHATTAN CORPORATION (Various Sleazy Businessmen)

Villains So Corporate They Probably Bill for Their Own Evil

The suits behind Ann’s capture are wonderfully one-note:

cold,

greedy,

power-hungry,

and allergic to natural lighting.

They barely appear, yet their presence hangs over the entire film like a boardroom full of cigarette smoke and moral bankruptcy.

They represent the film’s theme:

Corporate power is more dangerous than the Bronx.

CHARACTERS WHO SHOW UP, YELL ONE LINE, AND DIE

A cherished exploitation tradition.

Examples include:

the biker who dies mid-sentence in slow motion,

random Zombies who roll onscreen only to be punched offscreen,

that one dude who gets shot while doing a dramatic spin (pure cinema).

These bit characters give the Bronx its texture — disposable bodies in a disposable world.

INFLUENCES: A CINEMATIC DNA TEST

(A Glorious Patchwork of American Grit, Italian Spectacle, and Pure 80s Imagination)

If 1990: The Bronx Warriors took a DNA test, the results would crash the database. The movie is a collage of cinematic inspirations—some obvious, some deep-cut, all filtered through the delightfully unhinged sensibilities of Italian genre cinema.

Let’s break down the creative genealogy.

1. The Warriors (1979): The Godfather of Gangs in Costumes

The influence of Walter Hill’s cult epic is unmistakable:

Themed gangs in elaborate outfits

Quest-like structure as factions move through hostile territory

New York as a neon-lit urban myth

Where The Warriors was gritty yet hyper-stylized, Bronx Warriors says:

“What if every gang was dialed up to 11 and wearing Halloween costumes from a glam-rock thrift store?”

The Riders, the Tigers, and especially the roller-skating Zombies feel like cousins of the Baseball Furies — wackier, wilder, and decidedly more Italian.

2. Escape from New York (1981): Dystopia With a Government-Shrug Vibe

John Carpenter imagined Manhattan as a walled-off prison. Castellari took that premise and applied it to the Bronx:

A future where the government simply gives up on an entire borough

An urban wasteland ruled by tribes

Antihero leadership (Trash ≈ a very quiet Snake Plissken)

A sense that society collapsed and no one cleaned up afterward

The major difference?Carpenter’s vision was minimalist and brooding.Castellari’s is maximalist, loud, chaotic, and wearing studded leather.

3. Mad Max 2: The Road Warrior (1981): The Apocalyptic Fashion Designer of Cinema

Italian exploitation films of the early ’80s were so obsessed with Mad Max 2 that you’d think George Miller invented oxygen.

Influences include:

Spiky leather costumes

Punk rock aesthetics

Vehicular violence

Moral codes built on survival, not society

Chaotic, propulsive editing

The film’s biker stunts and junkyard-chic wardrobe are practically a love letter to Miller’s wasteland—just transplanted into a city of burning barrels and abandoned subway tunnels.

4. Italian Poliziotteschi Films (70s Crime Thrillers): Grit on a Budget

Italy had a rich genre tradition of gritty crime dramas long before the Bronx Warriors showed up.

Influences include:

nihilistic urban decay

corrupt authority figures

brutal street violence

anti-establishment themes

But where poliziotteschi films were angry and rough, Bronx Warriors is stylish and comic-booky. It’s the difference between a protest march and a glam-rock album cover.

5. Spaghetti Westerns (Psychology and Power Structures)

Fred Williamson’s Ogre feels like a Western warlord transported into a post-apocalyptic borough. His palace-like headquarters, his regal calm, and his dominance over the Tigers echo Western archetypes:

The charismatic tribal leader

The lawless frontier

The showdown justice

Trash and Ogre even share a classic “gunslinger meets kingpin” dynamic.

6. Comic Books & Heavy Metal Album Art

While not tied to one specific influence, the film’s visual vocabulary resembles:

70s/80s underground comics

the exaggerated post-apocalyptic imagery of Heavy Metal Magazine

fantasy art depicting gangs as mythic tribes

It’s stylized, theatrical, and intentionally unrealistic — the Bronx as a mythological world rather than a geographical location.

LEGACY & RECEPTION: HOW A TRASHY GEM BECAME A CULT ICON

(From Critical Punching Bag to VHS Legend to Beloved Midnight Movie)

The legacy of 1990: The Bronx Warriors is as strange and wonderful as the film itself. It did not arrive as a masterpiece. It did not win awards. It did not impress critics. But it survived — and sometimes, survival is the truest form of cinematic triumph.

1. Initial Reception: Critics Were… Not Kind

When the movie premiered, critics treated it like a contagious rash:

“Exceedingly silly”

“Derivative”

“Guilty of every exploitation cliché in the book”

“A movie made entirely of costume decisions”

Professional reviewers couldn’t see past the low budget, over-the-top acting, and chaotic plot. Mainstream audiences largely ignored it.

But as with many cult films, time proved that the critics were watching the wrong movie in the wrong mindset.

2. The Home Video Revolution: VHS Makes It a Star

Here’s where the film found its true destiny.

In the 80s and 90s:

VHS shelves were filled with neon explosions of weirdness

rental shops needed flashy, wild-looking covers

post-apocalyptic films were renting like crazy

The box art for Bronx Warriors — flaming motorcycles, leather gangs, the decaying skyline — made it irresistible on video store shelves.

It became a sleepover classic, a basement-watch favorite, and a late-night TV oddity for kids who loved action but weren’t ready for Schwarzenegger.

3. Cult Cinema Embrace: “It’s So Bad It’s Amazing”

By the 2000s, the film’s reputation had flipped:

midnight movie audiences embraced it

exploitation scholars reclaimed it

fans championed its sincerity and style

RiffTrax did a comedic commentary

boutique Blu-ray labels packaged it lovingly

People began to recognize that beneath the cheapness was a genuine artistic voice — a director who cared about images, rhythm, color, and energy.

It’s no longer judged by Hollywood’s standards, but by cult cinema’s:Is it fun? Is it stylish? Does it deliver unique vibes?Yes. Yes. Oh yes.

4. Preservation & Home Media: The Deluxe Treatment

Labels like Blue Underground and Arrow Video embraced the film and its sequel (Escape from the Bronx) with:

remastered transfers

liner notes

director interviews

behind-the-scenes features

gorgeous updated artwork

The fact that this once-dismissed exploitation flick now has a meticulous HD restoration is proof of its cult ascension.

5. Fan Culture: Trash, the Zombies, and the Ogre Live On

Online communities adore:

The Zombies’ absurd roller-skate armor

Trash’s pouty model-boy persona

The Ogre’s royal swagger

the synth soundtrack

the over-the-top costumes

the gleefully chaotic stunts

Cosplayers, meme-makers, and synthwave enthusiasts have kept the movie alive in unexpected ways.

It’s not just a film — it’s an aesthetic.

6. The Tragic Mystery of Mark Gregory Adds a Bittersweet Layer

Mark Gregory’s brief rise and disappearance from cinema adds poignancy to the film’s legacy. His story has been pieced together by fans over the years, lending the movie an unexpected emotional resonance. Trash’s lone-wolf persona feels more symbolic knowing his star faded so quickly.

7. Reassessment: From Trash Cinema to Cult Treasure

Today, the film isn’t judged for what it isn’t — it’s praised for what it is:

a stylish anomaly

a passionate low-budget experiment

a vibrant piece of exploitation history

a reminder that sincerity matters more than money

a prime example of Italian genre filmmakers doing their wildest, weirdest best

It’s not trying to be prestige cinema.

It’s trying to be cool — and somehow, it succeeds.

FINAL VERDICT

A Glorious, Ridiculous, Surprisingly Beautiful Mess

1990: The Bronx Warriors is:

dumb

brilliant

ugly

stylish

nonsensical

unforgettable

It is exactly the kind of movie that midnight screenings were invented for. It’s not a good film—but it’s a great one to watch.

⭐ Final Rating: 6.5/10

A flawed, lovable genre oddity that punches way above its weight…and then crashes its motorcycle in slow motion.

Comments