Smackdown in the Southern Hemisphere: The Rise, Fall and Banana-In-Pajamas Era of World Wrestling All-Stars

- Jan 24

- 27 min read

Buckle up, wrestling nerds: this is your deep dive — with a sprinkle of humor — into the roller-coaster life of World Wrestling All‑Stars (WWA). The good, the bad, the guitars, the Bananas in Pajamas, the losing streaks, and the legacy. Grab your popcorn.

Chapter 1. “Down Under, Gimmicks & Grand Ambitions”

The Wild Birth of the World Wrestling All-Stars (WWA)

Let’s rewind to the year 2001 — a time when wrestling fans everywhere were still recovering from what can only be described as the “Great Wrestling Consolidation.”

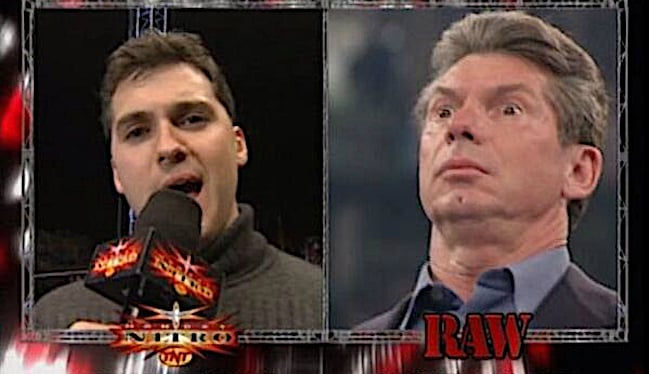

Two of the biggest wrestling promotions of the 1990s — World Championship Wrestling (WCW) and Extreme Championship Wrestling (ECW) — had just crashed and burned, leaving behind a wasteland of unemployed wrestlers, confused fans, and mountains of unused entrance music.

The Fall of WCW: The Billion-Dollar Titanic

WCW, once a genuine competitor to Vince McMahon’s WWF during the legendary Monday Night Wars, was a ratings juggernaut in the mid-’90s. Thanks to Ted Turner’s bankroll and stars like Hulk Hogan, Sting, Goldberg, Ric Flair, and the nWo, WCW beat WWF in the ratings for an incredible 83 consecutive weeks between 1996 and 1998.

But by 2000–2001, the company had imploded under:

Creative chaos (storylines that made no sense, constant reboots, and too many “powers that be”).

Financial hemorrhaging (Turner execs realized they were spending millions for declining ratings).

Corporate takeover madness (AOL Time Warner merger didn’t want “rasslin’” on its networks).

In March 2001, WWF (soon to be WWE) bought WCW for a fraction of its former value — reportedly $2.5 to $4 million for trademarks, tape library, and select contracts. Overnight, hundreds of WCW talents — from Jeff Jarrett to Buff Bagwell to Shane Douglas — were left without jobs or guaranteed TV exposure.

The Collapse of ECW: Hardcore Without a Home

Meanwhile, ECW, the Philadelphia-based cult favorite run by Paul Heyman, had been the rebellious, barbed-wire alternative for the previous decade. It was where names like Rob Van Dam, Sabu, Tazz, and Tommy Dreamer became legends.

But by 2000, ECW was financially gasping for air. Pay-per-view revenue wasn’t covering costs, TV deals fell apart (thanks, TNN), and the company’s final show, Guilty as Charged 2001, was less of a celebration and more of a funeral with folding chairs. Heyman famously appeared on WWF commentary only weeks later — wearing the smug grin of a man who brought a chair from the wreckage.

By spring 2001, both WCW and ECW were dead, and Vince McMahon’s WWF was the only major game in town.That left a massive pool of talent — wrestlers, referees, announcers, managers — all suddenly available, hungry, and looking for new places to work.

Enter Andrew McManus — The Aussie Promoter with a Crazy Idea

Now, across the Pacific, Australian concert promoter Andrew McManus saw opportunity in the rubble.McManus had made his money staging rock concerts (think Deep Purple, Blondie, and KISS), and he figured wrestling could be treated like a touring live spectacle — much like a traveling music festival, but with suplexes instead of guitar solos.

His vision:

Take the available ex-WCW and ECW talent (name recognition ✅).

Mix in some independent wrestlers and homegrown Aussies (freshness ✅).

Run big arena shows in Australia, New Zealand, the U.K., and North America (untapped international markets ✅).

Sell pay-per-views (extra revenue ✅).

He called his new baby World Wrestling All-Stars (WWA) — a name that screamed “We’ve got whoever we can afford this week!”

To his credit, McManus didn’t half-step it. He hired:

Jeremy Borash (former WCW personality) as the voice and creative hand behind the scenes.

Jerry Lawler, Bret Hart, and others for guest appearances early on.

Production crews familiar with large live events.

And in late 2001, as WWF was turning “Attitude” into “Ruthless Aggression,” WWA was pitching itself as the global alternative — “sports entertainment with a passport.”

The first event was titled “The Inception”, because, well, that’s what it was: the start of something new.Held at the Sydney SuperDome on October 26, 2001, it featured:

A ladder match for the Cruiserweight title between Juventud Guerrera and Psicosis.

A steel cage final for the inaugural World Heavyweight Title between Jeff Jarrett and Road Dogg.

Guest appearances by everything from mimes to Bananas in Pajamas.

It was flashy, chaotic, and a little ridiculous — but it worked enough to draw a strong local crowd.

The Wrestling World in Flux

WWA’s timing was both brilliant and terrible.

Brilliant, because there was a giant vacuum. Displaced fans wanted something other than WWE.

Terrible, because that vacuum existed for a reason — starting a global wrestling promotion from scratch without a weekly TV show was like trying to play football without a stadium.

Still, McManus saw untapped markets. While WWE was focused on North America, he aimed to make WWA a worldwide touring brand, running international shows featuring “all-stars” from around the globe.

And to be fair, the concept had charm:Fans in Australia got to see Sting, Jarrett, Steiner, and Sabu live — something that rarely happened before. It was like WCW on vacation, with palm trees and kangaroos.

But even early on, cracks were visible. Behind the pyro and nostalgia, there was little infrastructure, no long-term creative direction, and limited talent commitment.WWA didn’t have a TV deal, so stories existed only between sporadic pay-per-views — a bit like trying to binge-watch a show that only drops two episodes a year.

Chapter 2. “The Roster, the Ringers, and the Runaways”

Who Showed Up, Who Didn’t, and Who Cashed Their Check in U.S. Dollars Anyway

If WWA were a band, its roster was a rock festival lineup poster that looked amazing on paper — but half the headliners canceled, the sound system caught fire, and somehow the opening act stole the show.

Andrew McManus had one clear advantage over every other indie promoter at the time: there were suddenly hundreds of big-name wrestlers available after the collapses of WCW and ECW.He could raid the buffet of wrestling talent — the “All-You-Can-Sign” menu — and he did so with gusto.

🧓 The Nostalgia Main Event Crew — WCW’s Greatest Hits (and Misses)

WWA’s selling point from day one was star power. McManus and Jeremy Borash went for names that fans around the world would recognize — even if those names came with baggage, bad knees, or bloated egos.

Jeff Jarrett – The Guitar-Slinging Franchise

Jarrett wasn’t just WWA’s top heel; he was the guy holding the promotion together with duct tape and double-J bravado.He won the WWA World Heavyweight Title multiple times, carried storylines, did media rounds, and was basically the company’s spokesman, even when the company couldn’t decide if it was alive or undead.It’s worth noting: Jarrett was already quietly developing NWA-TNA while WWA was still running, which is both impressive and hilarious — he was building the promotion that would eventually absorb WWA’s titles.(Imagine Batman moonlighting as the Joker’s career counselor.)

Sting – The Legend with Frequent-Flyer Miles

Sting was the biggest “get” in WWA’s lineup — a WCW icon appearing in non-WWE rings again. He worked selective dates (mostly the European and Australasian tours) and was a consummate pro.His matches against Luger and Jarrett were main-event material by name value alone, even if sometimes they looked more like “gentleman’s exhibitions” than the high-octane brawls of old.Still, seeing Sting in Australia felt monumental at the time.

Scott Steiner – Big Poppa Pump and His Chainmail Hat of Doom

Steiner’s run was pure chaos — snarling promos, impressive physique, and the charisma of a man who genuinely believed every arena was his gym.He captured the WWA World Title at Eruption in Melbourne but soon vacated it to re-sign with WWE.WWA suddenly realized their world champion had just taken a one-way flight to Connecticut — not ideal for business.

Lex Luger – “The Total Package (Some Assembly Required)”

Luger joined later, during the U.K. tour, where he beat Sting for the vacant world title at Retribution. By that point, WWA was mostly running on nostalgia fumes, so getting Luger to work a decent match (with Sting’s help) was a coup.He looked the part — tan, musclebound, slightly bewildered — but his involvement screamed “one-last-payday-tour” more than “revolutionary comeback.”

Sid Vicious, Road Dogg, Buff Bagwell, and Disco Inferno

These names appeared sporadically, usually for comic relief or undercard filler.Sid was billed as an “enforcer,” Road Dogg served as Jarrett’s foil, Buff flexed and posed as only Buff can, and Disco danced like it was still 1998.Collectively, they gave WWA that distinct WCW Nitro-afterparty energy.

🚀 The Future Stars (Before They Were “Future Anything”)

While WWA’s main draws came from the old guard, its most exciting matches — and its true legacy — came from the younger, hungrier talents.

A.J. Styles – “The Phenomenon Before He Had Merch”

WWA gave Styles one of his earliest global PPV appearances. At Eruption in 2002, he won the WWA International Cruiserweight Title in a tournament by defeating Jerry Lynn — a match that still holds up today.The athleticism, crisp pacing, and chemistry between them foreshadowed what both men would bring to TNA’s X Division.If you squint, you can see WWA planting seeds for modern high-flyer wrestling.

Jerry Lynn – The Steady Hand of the Midcard

Lynn was the workhorse — the Bret Hart of every match he touched. Whether facing Styles, Juventud, or Nova, he delivered solid, technical performances that outclassed much of the upper-card chaos.WWA may have been clown shoes sometimes, but Jerry Lynn made those shoes dance.

Juventud Guerrera, Psicosis, and the Cruiserweight Crew

These two luchadores carried over their WCW rivalry to WWA and were the centerpiece of the first PPV’s ladder match.High spots, broken tables, and the type of aerial daredevilry that briefly made fans forget about the 47-minute Jeff Jarrett promo they’d just endured.Juventud’s ego was almost as big as his frog splash, but the man could go.

Sabu – The Human Botch Machine and Hardcore Icon

Sabu did what Sabu does — risk his life with every leap.His matches in WWA were messy masterpieces: chairs, tables, cages, and the occasional “oh-no-he-really-did-that.”He lent WWA credibility with the ECW crowd and gave the product an edge that it desperately needed.

Nova, Frankie Kazarian, and Low Ki

While not heavily featured on PPV, these guys worked the tours and showcased flashes of the independent style that would define wrestling in the 2000s.Kazarian and Low Ki later became key figures in the TNA/ROH pipeline, proving WWA had an eye (or at least a lucky dart throw) for talent.

🧳 The Great Talent Carousel — Who Left, Who Jumped, and Who No-Showed

One of WWA’s biggest headaches was keeping track of who was actually under contract — or even in the same time zone.The promotion’s slogan could’ve been “Card Subject to Change (Seriously, Every Card).”

Eddie Guerrero

Appeared at The Revolution in February 2002, stole the show by winning the Cruiserweight Title, and then… immediately left to re-sign with WWE. The belt was vacated faster than a hotel room at checkout time.

Scott Steiner

Won the world title, posed for cameras, then jumped to WWE before the next PPV. Classic Steiner move.

Randy Savage

Advertised as WWA’s big Las Vegas draw. Didn’t show. Fans were promised “Macho Man vs Jarrett” — got “Brian Christopher vs Jarrett.” Oof.

Bret Hart

Involved early in an authority role and promotional work but quietly disappeared once the first tour wrapped. (To be fair, he had other priorities after his WCW retirement.)

Road Dogg & Konnan

Made early appearances, then dipped for TNA bookings. Jarrett’s side hustle was basically poaching his own coworkers.

This revolving-door roster made consistent storytelling nearly impossible. One week, Steiner was champ; the next, Luger was. One month, Eddie was cutting promos; the next, he was on SmackDown.The WWA creative team must’ve had the world’s most stressful whiteboard.

🎬 The Backstage Picture — Booking, Borash, and “WWA Logic”

Behind the scenes, Jeremy Borash acted as the glue holding everything together — commentator, creative producer, sometimes ring announcer, sometimes damage-control expert.Borash’s vision leaned toward fast-paced international cards that combined spectacle with indie athleticism. Unfortunately, McManus’s team (concert guys, not wrestling guys) often thought “wrestling” just meant “add pyro and play loud music.”

The result?WWA shows looked like a weird hybrid of a rock concert, a mid-’90s WCW taping, and an episode of Gladiators filmed in a thunderstorm.

Storylines were often written on the fly — partly because they didn’t know who would actually show up.One infamous anecdote from the Revolution PPV: The production team found out live on show day that Randy Savage wasn’t coming. They scrambled to insert Brian Christopher in the main event and re-recorded promo packages backstage minutes before airtime.Borash reportedly joked, “We’ll call it The Revolution because every match rotates at least once before we know what’s happening.”

🔄 WWA → TNA: The Great Wrestling Recycle

As WWA sputtered into 2002-2003, many of its wrestlers migrated to Total Nonstop Action (TNA) — founded by none other than Jeff Jarrett himself.TNA learned from WWA’s mistakes:

Weekly TV (via PPV).

More coherent booking.

Focused X Division (an evolution of WWA’s Cruiserweight style).

By mid-2003, the overlap was so heavy that WWA’s roster looked like a TNA dark match card.When Jarrett and Sting met at The Reckoning (WWA’s final show), they weren’t just closing a promotion — they were literally passing its lineage into TNA.The WWA Heavyweight Title and Cruiserweight Title were both unified into TNA/NWA belts that night.

Symbolically, WWA’s talent pipeline became TNA’s foundation. So while WWA as a brand faded, its DNA lived on in the X Division, the international touring style, and the “ex-WCW meets indie upstart” formula that defined early-2000s wrestling outside WWE.

🪞 Final Thoughts on the Roster Circus

WWA’s roster was like a wrestling fan’s fever dream — all your favorite names, but slightly older, slightly shinier, and slightly confused about what country they were in.They couldn’t sustain momentum because every big name used the company as a stepping stone, not a home.

But hey — for a brief time, you could turn on a pay-per-view and see A.J. Styles, Scott Steiner, Sabu, and Buff Bagwell on the same card, in front of Australian fans chanting for Sting. It was wild, it was messy, and it was beautiful in that “backyard barbecue with pro wrestlers” kind of way.

Chapter 3. “Belt-Mania Down Under”

The Titles, the Turmoil, and the Time Jeff Jarrett Unified Everything That Moved

If wrestling championships are supposed to symbolize prestige, lineage, and excellence, then the World Wrestling All-Stars titles symbolized something slightly different:👉 “Whoever showed up that night and didn’t already have a WWE contract.”

Let’s take a tour through WWA’s colorful championship landscape — where every belt had a story, and every story usually ended with someone boarding a flight to Orlando.

The WWA World Heavyweight Championship — A Belt with Commitment Issues

The WWA World Heavyweight Title was the company’s crown jewel… or at least, the shiniest prop they had available at the time. It was introduced at WWA’s inaugural event, The Inception, in October 2001 in Sydney, Australia.

The plan was simple: crown a new world champion, showcase major stars, and make fans believe this was the next big global title.

The execution? A little less polished.

The Inception (Oct 2001)

The tournament culminated in Jeff Jarrett vs. Road Dogg (B.G. James) inside a steel cage.

Jarrett, armed with his trusty guitar and a smirk powered by pure Memphis energy, captured the inaugural title.

Bret Hart appeared to present the belt and cut a heartfelt promo about the “new era of wrestling.”(Ironically, that “new era” lasted about as long as one of Buff Bagwell’s tag teams.)

Jarrett’s reign gave the title credibility — but it also started a pattern that became peak WWA logic:whoever was the most reliable headliner at the moment became champion, even if the storyline continuity made zero sense.

A Title History (and Geography) Lesson

WWA ran just five pay-per-views, and somehow managed to crown or vacate their world title five times. Let’s break it down:

The Inception (Oct 2001 – Sydney, AUS)

Champion: Jeff Jarrett

Defeated: Road Dogg Reign Length: Until… well, he needed a break.

The Revolution (Feb 2002 – Las Vegas, USA)

Vacant due to Jarrett’s absence (and possibly a booking dispute).

New Champion: Scott Steiner Defeated: Nathan Jones (yes, that Nathan Jones, future WWE giant and acting extra in Mad Max: Fury Road).

Fun fact: Steiner won the belt, posed for photos, then immediately jumped to WWE without ever defending it. WWA’s world title defense record at that point: zero.

Eruption (Apr 2002 – Melbourne, AUS)

Vacant again (Steiner’s gone, shocker).

Champion crowned: Nathan Jones defeated Scott Steiner’s shadow (kidding — he beat Jeff Jarrett in the storyline, though Steiner’s absence forced creative rewrites). Jones, a legit Aussie powerhouse, looked like a star… until he too left for WWE before the next show.

WWA was basically WWE’s pre-signing tryout by this point.

Retribution (Dec 2002 – Glasgow, UK)

Vacant once again. (If you’re sensing a pattern, congratulations — you’re qualified to book WWA.)

New Champion: Lex Luger defeated Sting in a match promoted as “The Total Package vs. The Icon.”Both were WCW legends; both gave about 75% effort. Still, for U.K. fans, it was a nostalgia trip worth the ticket price.

Luger became champion — but by early 2003, he wasn’t appearing regularly either.

The Reckoning (May 2003 – Auckland, NZ)

Vacant for what felt like the tenth time, WWA’s final PPV saw Jeff Jarrett reclaim the throne.

Jarrett defeated Sting again, in a rematch that doubled as the official unification of the WWA World Title with the NWA World Heavyweight Championship, under the TNA banner.

Symbolically, this was Jarrett burying one company to feed another — the snake eating its own tail, but with more pyro.

A Title Built on Travel Points and No-Shows

If you tracked the WWA title geographically, it went something like this:

Sydney → Las Vegas → Melbourne → Glasgow → Auckland → Oblivion.

Every champion either:

Left for WWE.

Was unable to travel for the next show.

Was replaced mid-tour.

And yet — through sheer resilience and charisma — Jeff Jarrett somehow made it all work. He was the constant face of the promotion, the one man who could walk out and make the fans believe the belt still mattered, even if it had changed hands more times than a customs declaration.

The WWA International Cruiserweight Championship — Where the Real Wrestling Happened

Now this belt? This one slapped.

The WWA International Cruiserweight Championship was the promotion’s secret weapon — fast-paced, athletic, and surprisingly well-booked compared to the heavyweight circus.

The Inception (2001):

The title was introduced with a Juventud Guerrera vs. Psicosis ladder match, which was legitimately awesome. It set the tone for what would later become TNA’s X Division — “it’s not about weight limits, it’s about no limits.”

Juventud won the match and the belt, becoming the first Cruiserweight Champion. (He also cut an unfiltered post-match promo that went completely off-script — pure Juvi energy.)

The Revolution (2002):

Eddie Guerrero made a surprise appearance and defeated Juvi for the title in Las Vegas. The crowd popped hard — Eddie was a legit star, and the match had that ECW/WCW nostalgia mixed with technical brilliance.

Unfortunately, Eddie re-signed with WWE shortly after, forcing WWA to vacate the title. Again.

Eruption (2002):

A Cruiserweight Tournament was held to crown a new champ, featuring A.J. Styles, Jerry Lynn, Nova, and Chris Sabin (yes, that Chris Sabin).

A.J. Styles defeated Jerry Lynn in the final — an early classic that hinted at the chemistry the two would later showcase in TNA. Styles was young, fast, and everything WWA needed more of. Sadly, his reign didn’t last long either — he too moved on to TNA by the end of the year.

By 2003, the Cruiserweight Title was quietly merged into the TNA X Division, where its spirit lived on. In a poetic way, that lineage made sense — the best of WWA’s in-ring legacy became the blueprint for TNA’s greatest innovation.

The WWA Tag Team Championships — “Wait, We Had Those?”

Ah yes, the forgotten children of WWA’s belt collection.

The Tag Team Titles were announced early on, even designed — but rarely defended.

A few teams popped up during the tours:

Road Dogg & Konnan teamed briefly (and loudly).

Buff Bagwell & Stevie Ray did some comedy work.

The Stooges (yes, literal comedians in masks) were used for filler matches.

But official title reigns? Good luck finding consistent documentation.The belts appeared briefly in 2002, disappeared by 2003, and were never unified or mentioned again. They were like the Bermuda Triangle of championship belts — you heard they existed, but no one ever saw them twice.

Booking Chaos & “The Belt That Time Forgot”

A recurring WWA theme was vacancy — not just in titles, but sometimes in logic.Because the promotion ran so infrequently, titles became less about continuity and more about drawing power:

“Who’s available and looks good on the poster? Cool, give them the belt.”

This led to several surreal moments:

Steiner being announced as champion after leaving the company.

Nathan Jones holding the title on paper while training in WWE’s developmental system.

Sting and Luger’s matches being advertised as “title bouts” even when no one was sure which belt they were fighting over.

Borash later joked in interviews that sometimes they’d “book the belt backwards” — meaning they’d announce a championship match before deciding who was actually champion that week.

The Final Unification — The Reckoning (2003)

WWA’s swan song in Auckland, New Zealand, was actually a fitting finale.The show featured:

Jeff Jarrett vs. Sting for both the WWA and NWA World Heavyweight Titles.

Chris Sabin vs. Jerry Lynn vs. Frankie Kazarian vs. Johnny Swinger to unify the WWA Cruiserweight Title with the TNA X Division Championship.

Jarrett defeated Sting, officially merging the belts — a torch-passing moment from one ambitious startup to another.

Sabin won his match as well, cementing the Cruiserweight/X Division connection.

It was poetic in its own chaotic way: WWA’s final act was to give its lineage and legacy to the company that would actually survive.

WWA’s Belt Legacy: A Short, Shiny Life

When you zoom out, WWA’s championship scene looks like the perfect metaphor for the promotion itself:

Big ambitions.

Inconsistent execution.

Occasional brilliance.

And a revolving door of talent that never stayed long enough to build momentum.

But the impact was real.The Cruiserweight division directly inspired the TNA X Division, and the world title’s unification made WWA’s existence part of official NWA history — however briefly.

So while the belts may have bounced around like hot potatoes, they still left fingerprints on the next generation of wrestling.

Chapter 4. “From Popcorn to Pyro: The WWA Show Timeline”

Every Pay-Per-View, Every Pop, Every Powerbomb That Hit the Mat (and Some That Didn’t)

WWA’s five pay-per-views were like episodes of a bizarre, world-traveling wrestling sitcom — each with its own cast changes, production quirks, and “Wait, is that guy still champion?” moments.

What follows is a blow-by-blow timeline of each event, the key storylines, title changes, and general madness that made WWA both fascinating and fleeting.

The Inception — October 26, 2001 (Sydney, Australia)

Tagline: “A New Era Begins Down Under!”

Venue: Sydney SuperDome

Attendance: Roughly 8,500 rowdy Aussies

PPV Commentary: Jeremy Borash & Jerry Lawler

This was the big one — the launch of Andrew McManus’s vision for an international wrestling super-show. Australia hadn’t seen an event of this scale since the WWF tours of the 1980s, and McManus went all out: lasers, pyro, live music, and more leather pants than a Bon Jovi concert.

Highlights:

Juventud Guerrera vs. Psicosis (Ladder Match) — The best match of the night by a mile. High spots galore, crowd-pleasing insanity, and a finish that saw Juvi capture the inaugural WWA International Cruiserweight Title.

Sabu vs. Devon Storm (Crowbar) — Equal parts car crash and art project. Tables, chairs, broken bones, and Sabu doing Sabu things.

Bret Hart made an emotional appearance as “Commissioner,” dedicating the event to the late Owen Hart. It gave the show a touch of legitimacy and heart.

Main Event: Jeff Jarrett vs. Road Dogg (Steel Cage Match) — It wasn’t pretty, but it was nostalgic. Jarrett won the inaugural WWA World Heavyweight Title with a guitar shot that could be heard in Perth.

Post-Show Buzz:

Fans loved the nostalgia and spectacle. Critics loved the Cruiserweight match. Nobody was entirely sure what WWA’s storylines were — but hey, it was fun.The show proved there was an audience for a WCW-style product outside North America.

The Revolution — February 24, 2002 (Las Vegas, USA)

Tagline: “The Revolution Will Be Televised… Eventually.”

Venue: Aladdin Casino, Las Vegas

Commentary: Jeremy Borash & Jerry Lawler

WWA went stateside for its second show, hoping to make a splash in the U.S. market. Unfortunately, the splash sounded more like a light drizzle.

Highlights:

Eddie Guerrero vs. Juventud Guerrera — The match that stole the show. Eddie won the Cruiserweight Title in a technical gem that briefly made fans forget they were watching a show where the main event got changed on the day.

Road Dogg vs. Lenny Lane (with Lodi) — A comedy-heavy filler match that featured more mic work than wrestling. The fans were… forgiving.

Sabu vs. Devon Storm (again!) — Yes, they ran it back, because chaos never goes out of style.

Main Event (Originally advertised: Jeff Jarrett vs. Randy Savage) — Except Savage didn’t show up. Cue Brian Christopher (Grandmaster Sexay) being inserted at the last minute to face Jarrett instead. Jarrett won, of course, and everyone went home confused but mildly entertained.

Fun Fact:

WWA actually filmed two alternate endings for this show because they weren’t sure if Savage would arrive. He didn’t, so one of those endings became wrestling’s weirdest collector’s item: “WWA Main Event Featuring Randy Savage’s Absence.”

Post-Show Reaction:

Fans were baffled but amused. The Cruiserweight match drew praise, but the rest of the card felt like a WCW Thunder episode that got lost in the desert.Still, WWA wasn’t dead — yet.

Eruption — April 13, 2002 (Melbourne, Australia)

Tagline: “Feel the Heat!”

Venue: Rod Laver Arena

Commentary: Jeremy Borash & Stevie Ray

Back home in Australia, WWA delivered what many fans consider their best show. The production was tighter, the crowd was hot, and — miracle of miracles — most of the talent actually showed up.

Highlights:

Cruiserweight Tournament:

A.J. Styles, Jerry Lynn, Nova, and Chris Sabin tore the house down.

The final: A.J. Styles defeated Jerry Lynn in a match that felt ten years ahead of its time.

Styles was crowned the new WWA Cruiserweight Champion, marking one of his first major international title wins.

Jeff Jarrett vs. Nathan Jones — Jarrett dropped the WWA World Title to the towering Australian powerhouse. The crowd went wild for their hometown hero.Unfortunately, Jones signed with WWE almost immediately after — forcing yet another title vacancy.

Sabu vs. Devon Storm (No DQ Match) — It was violent, it was nuts, and it was… well, a Sabu match.

Stevie Ray on commentary provided unintentional comedy gold, including several moments where he seemed to forget he was on air.

Post-Show Buzz:

Critics actually liked this one.The Cruiserweight tournament drew rave reviews and planted the seeds for what would become the TNA X Division just months later.

Retribution — December 6, 2002 (Glasgow, Scotland)

Tagline: “The Battle for the Belt Continues!”

Venue: SECC Arena

Commentary: Jeremy Borash & Mike Sanders

By this point, WWA’s touring model was running on fumes. Many wrestlers had moved to WWE or TNA, and the company leaned heavily on nostalgia to fill arenas. Still, they put on a decent show for the U.K. crowd, who were hungry for wrestling.

Highlights:

Lex Luger vs. Sting (for the Vacant WWA World Title) — Two legends, one nostalgia bomb.The match wasn’t exactly a five-star clinic — it was more “slow dance with headlocks” — but fans loved seeing their WCW favorites.Luger won the belt with his Torture Rack finisher, becoming the new champion.

Puppet the Psycho Dwarf (yes, really) cut a promo mid-show that somehow got over.

Sabu vs. Joe E. Legend — A surprisingly good hardcore match that woke the crowd back up.

Post-Show Buzz:

Mixed. The nostalgia factor worked, but production quality and pacing dragged. WWA was clearly struggling to find a direction — too serious for parody, too chaotic for consistency.

The Reckoning — May 25, 2003 (Auckland, New Zealand)

Tagline: “The Final Showdown”

Venue: North Shore Events Centre

Commentary: Jeremy Borash & Mike Tenay (on loan from TNA)

And so it came to this — the final WWA show, a co-produced event with TNA that served as both a finale and a transition of power.

Highlights:

Cruiserweight Unification Match: Chris Sabin vs. Jerry Lynn vs. Frankie Kazarian vs. Johnny Swinger Sabin won to unify the WWA Cruiserweight Title with the TNA X Division Title, officially ending WWA’s cruiserweight lineage.

Jeff Jarrett vs. Sting (Title Unification Main Event) This match was surprisingly solid — two pros who respected the moment.Jarrett retained his NWA World Title and absorbed the WWA World Title, effectively merging the companies’ lineages.

Jeremy Borash gave an emotional send-off to the fans, thanking Australia, New Zealand, and the U.K. audiences for believing in the “world tour of wrestling.”

Post-Show Buzz:

Fans called it the “best farewell show no one saw.”WWA quietly folded after this event, with no press release — its belts and legacy absorbed into TNA, and its name fading into the sunset like a midcarder’s entrance pyro.

In Retrospect: The Shows Were a Beautiful Mess

Each WWA event was an experiment — part wrestling show, part nostalgia convention, part rock concert fever dream.

Sometimes it clicked (Eruption).

Sometimes it stumbled (Revolution).

Sometimes it ended with Jeff Jarrett smashing a guitar over someone’s head and yelling “Slapnuts.”

But collectively?They were a fascinating snapshot of wrestling’s transitional era — between the Attitude Era chaos and the rise of independent-style athleticism.

Chapter 5. The Fall of the WWA: Where the Wheels Came Off (and the Kangaroos Jumped Ship)

The anatomy of a wrestling promotion that ran out of gas, cash, and wrestlers — but never out of chaos.

By mid-2003, the World Wrestling All-Stars wasn’t so much dying as it was slowly deflating.What started as an audacious world tour of wrestling — packed with pyro, nostalgia, and international flair — was now a ghost ship of absentee wrestlers, half-filled arenas, and a creative direction that could best be described as “let’s just see who shows up.”

But to understand why WWA failed, you need to look at all the cracks that formed beneath its flashy surface.

The Money Problem: “Touring Ain’t Cheap, Brother”

Andrew McManus, to his credit, came from the live music world — and in concerts, the business model is simple:You book a big name (say, KISS), sell out an arena, and go home rich in confetti and tinnitus.

Wrestling? Not so simple.

WWA tried to tour internationally — Australia, New Zealand, the UK, and the U.S. — without a weekly TV show.That meant every PPV had to sell cold to local markets. There was no continuity, no ongoing storylines, and no consistent TV advertising.

Every new event was like trying to sell a sequel to a movie no one saw.

Add in:

Flying in dozens of wrestlers from around the world,

Paying for production, insurance, customs, and arenas,

Plus McManus’s rock-show-level staging and lighting setups…

… and you’ve got a recipe for a very expensive world tour with very unpredictable returns.

Some shows (like Eruption in Melbourne) turned a profit.Others (Revolution in Vegas) were financial disasters. By 2003, WWA was reportedly losing money faster than Jeff Jarrett could swing a guitar.

The Talent Problem: “Everybody’s Got a Better Offer”

WWA’s original roster read like a who’s who of “free agents with name value”:

Jeff Jarrett

Road Dogg

Sabu

Scott Steiner

Juventud Guerrera

Lex Luger

Bret Hart (in a non-wrestling role)

But WWA’s biggest problem? It didn’t own anyone.

There were no exclusive contracts. Wrestlers worked show-to-show, meaning McManus could never guarantee who would appear next month.

And as soon as WWE or the newly founded Total Nonstop Action (TNA) offered these wrestlers longer deals or U.S. TV exposure — they were gone faster than a cruiserweight bumping for Sabu.

Let’s run the timeline of attrition:

2001: Jarrett, Road Dogg, and Juvi carry the brand.

2002: A.J. Styles debuts — and then signs full-time with TNA.

2002: Nathan Jones wins the world title — then jumps to WWE.

2003: Chris Sabin and Jerry Lynn headline — both under TNA contracts.

By 2003: Half the “World Wrestling All-Stars” were actually TNA wrestlers on loan.

By the end, WWA wasn’t even booking its own storylines — it was integrating TNA angles. The Reckoning PPV literally ended with Jarrett unifying the WWA and NWA titles, symbolizing that WWA had become TNA’s unofficial prequel.

The Creative Problem: “Too Many Gimmicks, Not Enough Storylines”

Let’s be honest: WWA’s creative direction was… an experience.

With Jeremy Borash calling the shots backstage and Andrew McManus steering the overall vision, the product had an identity crisis. Was it supposed to be a legitimate wrestling alternative? A nostalgia act? A touring rock circus? A parody of American wrestling?

Answer: all of the above — sometimes in the same show.

WWA leaned heavily on comedy segments, over-the-top gimmicks, and wacky matches, such as:

“Hardcore Midget Matches” featuring Puppet the Psycho Dwarf,

The “Human Cage Match” (don’t ask),

Musical performances between matches,

And multiple appearances by “The Commissioner,” who was sometimes Bret Hart and sometimes… not.

Without weekly TV, feuds felt random and rushed. One minute Sabu and Devon Storm were trying to kill each other, and the next, they were tagging together against different opponents. You couldn’t follow WWA storylines even if you wanted to.

It was like someone kept shuffling the deck between episodes.

The Exposure Problem: “No TV, No Continuity, No Chance”

Perhaps the biggest death blow of all: WWA had no weekly television presence.

WWE had Raw and SmackDown. TNA had Impact on pay-per-view.

WWA had… pay-per-views that aired once every few months, often in different continents, with no build or recap in between.

This made it impossible to create ongoing fan investment.

Even fans who liked WWA’s shows didn’t know when the next one would air — or who’d even be there.

WWA tried to compensate with slick video packages and heavy promotion through international channels, but it couldn’t replicate the week-to-week storytelling fans had grown used to during the Monday Night Wars.

And without that emotional investment, audiences drifted.

The TNA Factor: “The Younger, Hungrier Sibling”

Ironically, the company that helped end WWA was the one that shared its DNA the most: Total Nonstop Action Wrestling (TNA).

Founded in mid-2002 by none other than Jeff Jarrett and his father Jerry Jarrett, TNA had many of the same players — Borash, Styles, Lynn, Sabin, etc. — but with a crucial difference:weekly pay-per-view shows.

TNA offered consistent exposure, a deeper roster, and U.S.-based TV production.

So when WWA’s touring model became unsustainable, Jarrett smartly used WWA’s international platform to boost TNA’s visibility overseas. By The Reckoning, WWA’s final PPV, the writing was spray-painted in nWo-sized letters: WWA was done, and TNA was the future.

The Quiet Death

Unlike WCW or ECW, there was no dramatic collapse, no on-screen farewell.After The Reckoning in May 2003, WWA simply… stopped running shows.

No announcements. No official “closure.”Just silence.

Its final act — Jarrett unifying the WWA and NWA titles — was both symbolic and practical.TNA had inherited its wrestlers, its belts, and its purpose.

The “World Wrestling All-Stars” were now just wrestling stars, scattered across promotions, carrying with them the strange legacy of a promotion that aimed for the moon and landed somewhere in the Outback.

Chapter 6. Legacy of the WWA: The Promotion That Wasn’t Supposed to Work — and Kind of Did

You might think WWA left no mark.After all, it’s barely mentioned today except as a wrestling trivia footnote.

But in reality? It helped bridge eras — from the chaotic collapse of WCW and ECW to the rise of TNA and the indie wrestling boom.

Let’s give credit where it’s due.

It Proved There Was a Global Wrestling Market

Before WWA, few promotions had run full-scale tours in Australia, New Zealand, and the U.K. outside of WWE.WWA showed there was serious fan appetite for live events in those regions — paving the way for future tours by WWE, TNA, and eventually AEW.

It also exposed global audiences to new stars like A.J. Styles, Jerry Lynn, and Chris Sabin years before they became household names to wrestling diehards.

It Laid the Groundwork for the TNA X Division

WWA’s cruiserweight division was stacked with talent who would go on to define TNA’s signature style:

A.J. Styles

Jerry Lynn

Chris Sabin

Frankie Kazarian

Juventud Guerrera

The fast-paced, athletic, risk-heavy approach those guys brought to WWA was essentially the prototype for the X Division, which became TNA’s calling card.

Without WWA, that style might not have found its early mainstream footing.

It Was the First Post-WCW “Alternative”

Before ROH, before AEW, before the streaming era — WWA tried. It saw the hole left by WCW’s death and said, “We can fill that.”

Sure, it was rough around the edges.Sure, the booking was chaotic.Sure, it felt like a traveling carnival with powerbombs.

But for a few years, WWA was the only global alternative to WWE. It kept wrestlers working, kept fans engaged, and kept hope alive that wrestling could be bigger than one monopoly.

It Left Us with Glorious Weirdness

Let’s not pretend the legacy isn’t also hilariously bizarre.Where else could you find:

A mime manager named “The Fruits in Suits”?

Puppet the Psycho Dwarf threatening to fight Bret Hart?

Nathan Jones winning a world title and then immediately leaving?

Lex Luger wrestling Sting in 2002 and somehow being the heel and the babyface at once?

WWA gave us wrestling’s strangest scrapbook — and we’re better off for it.

Final Thoughts: The Promotion That Dared to Exist

WWA wasn’t perfect. It wasn’t even consistent.But it was brave.

In a time when wrestling fans were told “it’s WWE or nothing,” WWA said,

“Nah, mate — let’s run an arena in Sydney, bring in Jeff Jarrett, and see what happens.”

And for a fleeting moment, it worked.

The World Wrestling All-Stars didn’t just give us matches — it gave us memories, momentum, and the first step toward rebuilding a multi-company wrestling landscape.

So the next time you watch TNA, ROH, AEW, or even NJPW run a big international card?Tip your hat to Andrew McManus and his traveling circus of suplexes.They were the madmen who went first.

Chapter 7. Epilogue: From Slapnuts to Superkicks — The Ghost of WWA Lives On

Or: How a defunct Australian wrestling company from 2003 accidentally shaped modern wrestling’s global boom.

If you blinked, you probably missed it.If you sneezed, you definitely missed it.But the World Wrestling All-Stars wasn’t just a blip on wrestling’s radar — it was the static between two eras.

WWA existed in that weird, awkward teenage phase of pro wrestling:post-Attitude Era, pre-streaming age, when every wrestler still had a MySpace page and thought tribal tattoos were a solid life choice.

But in hindsight? The whole experiment feels… kind of important.

The Timeline No One Talks About (But Should)

Let’s connect the dots:

2001: WCW and ECW die. Wrestling fans everywhere panic.

2001-2003: WWA rises from the ashes, touring the world, putting on shows in Australia, the UK, and beyond.

2002: Jeff Jarrett says, “Why not start something called TNA?” — and brings half the WWA crew with him.

2004: Ring of Honor gains steam, featuring the same kind of high-speed wrestling that WWA’s cruiserweights showcased.

2010s: Indie wrestling explodes, global promotions collaborate, and the internet makes wrestling international again.

2019: AEW launches — a company built on the same “alternative wrestling” spirit that WWA tried (and hilariously struggled) to capture.

WWA was, in many ways, the prototype for the wrestling world we have now — messy, global, creative, and free from one-company domination.It’s like that weird garage band in the ’90s that broke up after one album… but everyone in it went on to join bigger, better bands.

WWA Walked So AEW Could Run (and So TNA Could Limp Competitively for Two Decades)

You can draw a straight line from WWA to TNA to AEW.

WWA proved there was a global appetite for wrestling outside of WWE.

TNA took that same energy and turned it into a weekly TV product.

AEW perfected the formula with streaming, production, and — let’s be honest — fewer mimes.

In an alternate universe, if WWA had snagged a TV deal and maybe not spent its pyro budget on Lex Luger’s tanning lotion, who knows?We might be talking about WWA Dynamite on Wednesday nights instead of AEW.

Jeff Jarrett: From Slapnuts to Wrestling’s Forrest Gump

If there’s one man whose fingerprints are all over this story, it’s Jeff Jarrett.

Jarrett was WWA’s first and last world champion, its most consistent draw, and its most enthusiastic guitar salesman.He took WWA’s ashes, built TNA from its skeleton, and somehow — somehow — ended up working for AEW in 2025, smashing guitars on national TV like it’s still 1999.

At this point, Jeff Jarrett isn’t a wrestler; he’s a multiversal constant.Promotions rise, fall, rebrand, and implode — but Jeff Jarrett remains.

A Legacy in Spirit (and in GIF Form)

What’s left of WWA today?No belts. No tapes in circulation (at least not legally).Just a handful of blurry YouTube clips, a few DVDs buried in bargain bins, and the lingering legend of “the Australian WCW.”

But every time you see a global supercard, a crossover event, or a pay-per-view in front of an international crowd — there’s a little bit of WWA in the DNA.

Every time AEW runs Wembley Stadium, or NJPW teams up with an American promotion, or a small indie runs a sold-out show halfway across the world, you can almost hear Andrew McManus in the distance yelling,

“Told ya it’d work, mate!”

And somewhere in the back, Jeremy Borash is holding a mic, Jeff Jarrett’s tuning a guitar, and Sabu’s trying to set a table on fire.

Final Thoughts: The Beautiful Madness of Trying

WWA didn’t fail because it was bad. It failed because it wasn’t built to last.

It was wrestling’s version of a summer blockbuster that blows its entire budget on the first explosion — fun, loud, ambitious, and destined to fizzle.But for two wild years, it kept wrestling’s spirit alive when WWE looked like it would swallow everything.

And that? That’s worth remembering.

Because the heart of pro wrestling has always belonged to the dreamers — the promoters who believe they can take on giants, the wrestlers who believe they can reinvent themselves, and the fans who keep showing up even when the ring ropes sag and the mic cuts out mid-promo.

WWA tried, and for a while, that was enough.

In Loving Memory of the World Wrestling All-Stars (2001–2003)

“Gone but not forgotten — mostly because Jeff Jarrett keeps bringing it up.”

Comments